The Other Badlands

I spend a lot of time in the desert, more specifically, in the badlands of the San Juan Basin. And, of the nine recognized badlands located there, I usually find myself wandering in either the Bisti Wilderness, or Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash. But, I want to step out of the box here and give a nod to the rest: the Ojito Wilderness, Mesa de Cuba, San Jose, Lybrook, Mesa Penistaja, Ceja Pelon, and De Na Zin.

Sedimentary rocks strewn haphazardly across bentonite mounds just inside the boundary of the Ojito Wilderness

What exactly is a badland? Merriam-Webster defines it as: a region marked by intricate erosional sculpturing, scanty vegetation, and fantastically formed hills–usually used in plural. The pre-requisites for a badlands to form are a grouping of harder sedimentary deposits: sandstone, siltstone etc. suspended in a softer matrix. As the softer material is eroded away, the harder, more dense material is left exposed, often perched on pedestals of the soft matrix.

But, at times the harder deposits may just be scattered haphazardly across a playa or alluvial plain or they may be isolated and in unexpected angles of repose. The seemingly inexplicable arrangement of the features is part of the mystique of the badlands. How did they get here and why? The answer to that question could fill a Geology text, and I am not even remotely qualified to go there. I can say, with some authority however, that the photographic possibilities are as close to infinite that you can get.

As you can imagine, the creation of such an environment takes time…a lot of time. Mesa de Cuba, the youngest is 38-54 million years old. San Jose is 48-64 million years old, Lybrook, Ceja Pelon, and Penistaja are all 60-64 million years old, De Na Zin, along with Bisti and Ah Shi Sle Pah, is 70-75 million years old, and Ojito is the oldest at 144-150 million years old. Each of the aforementioned locations have their own personality, and each of them offer there own version of timeless beauty.

Color is an element that often takes center stage in the badlands. Depending on the mineral content of the soil, there may be layers of red, yellow, blue, or even green. Combine this palette with the other strange and, often, unexpected elements of the landscape and the other-worldly, remote locations become even more surreal.

Possibly the most noticeable feature of such environments are the many erosion channels and drying cracks that cut into the soft bentonite, and mudstone that form the matrices that support the entire system. When the light is right, they stand out in stark relief revealing an almost unimaginable complexity.

As I already pointed out, most of these locations are much smaller than their more famous big brothers: Bisti, and Ah Shi Sle Pah. But, what they lack in size, they make up for in their diversity and surreal beauty. When you add to that the knowledge that these environments have been so many eons in the making (that petrified log emerging from the side of that bentonite mound was a cypress tree in a Mesozoic swamp), and are ever evolving (those sandstone slabs you just walked over will be the caprocks of hoodoos in some distant, future landscape), exploring and photographing them becomes even more significant and mysterious.

Just as you can never step into the same river twice; because of their fragile, and ever-changing nature, you can never visit the same badlands twice.

Springtime In Arizona

I have been planning a trip to southern Arizona to capture the spring wildflowers in bloom for several years. Something else always seemed to take priority. This year I finally just packed the car and started driving. I went first to Tucson where I lived for a short time in the late 70s. I was looking forward to seeing the place again.

The town has changed a great deal in the ensuing years. The places I could recognize were lost in a miasma of new construction, freeway signs, and traffic that bore little resemblance the place I remembered. I fled to the desert, which was really the point of the trip after all. Getting out of town took way longer than it should have, but I finally made it to Saguaro National Park where I spent the remainder of my first day lost in the healing process of making images.

I spent ten hours driving, walking, and making photographs. I wasn’t as excited as I should have been. The clear blue Arizona sky was boring, as was the light, especially at mid-day. As the sun moved lower in the sky, I noticed some clouds building on the western horizon; they were infused with a magnificent orange glow. I pulled over at a likely spot, parked the car and wandered into the desert. I had a specific image in mind and, as I walked through the cactus forest, I found what I was looking for. Teddy Bear Chollas have a kind of ephemeral quality about them, especially when they are backlit. The light shining through the clustered spines creates a halo of luminescence around them. Their soft, fuzzy appearance belies the reality, Those spines are barbed, and if you are unlucky enough to come too close, the result can be quite painful.

After a day shooting in Saguaro National Park, followed by another long drive back into Tucson (long due to traffic, not distance), I decided to head north towards Phoenix in hopes of finding more wildflowers. It was not a lack of quantity, or quality that fueled my decision; there was plenty of brittlebush blooming in the Tucson area, but I was really hoping to find some Mexican Poppies.

I took the back roads through Oracle, Arizona–one of my favorite writers, Ed Abbey, spent some time there in his later years. On the way I spent part of the day visiting Biosphere 2, before continuing on my way in search of photographs. I eventually arrived at Lost Dutchman State Park near Apache Junction a couple of hours before sunset. Once again, I found myself wandering through stands of cholla and Saguaros waiting for the sun to fall below the horizon. Besides the thrill of the pursuit of images, the experience of solitude in a remarkable landscape is one of the most rewarding aspects of a trip like this.

On the way home I stopped in Winslow, Arizona to pose with Jackson Browne. “Standin’ on a corner in Winslow, Arizona…”

I never did find the poppies, but all in all, it was a worthwhile trip. I managed to make some nice photographs, and to visit some old friends who live in Phoenix. On the way home, I stopped at a corner in Winslow made famous in song. The statue and “park” are the most noteworthy things I saw in the town, although friends have informed me that there is a good restaurant in one of the old hotels. Maybe I’ll check it out when I return in search of the poppies next year.

The Badlands Of The San Juan Basin

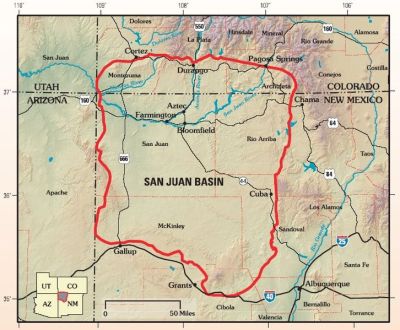

The San Juan Basin is a large, roughly circular, depression that lies in the northwest corner of New Mexico, and is a part of the larger Colorado Plateau. What makes the basin special is the fact that, at one time, it was in an area that was covered by the Western Interior Seaway, a prehistoric body of saltwater that split the North American continent from top to bottom.

The location along the shores of a large body of water in a tropical climate allowed an incredibly diverse ecosystem to thrive. As these life forms died, they decomposed and were eventually covered by volcanic ash from the eruption of nearby volcanoes. As the seawater covered the area more sedimentation sifted over the remains and some of the sediment was infused with mineral rich water that seeped through the layers above making it harder than the surrounding matrix. This was an important step in the formation of the present-day hoodoos. The weight of the water compacted the entire assemblage, and it was lost to the the world above the waves.

About 65 million years ago, the waters receded and a layer of sediment nearly two miles thick was left behind. Since then, plate tectonics, volcanism, and glacial erosion have helped to shape the present-day San Juan Basin. Further erosion from wind, water, and annual freeze/thaw cycles exposed the hardened sediment layers which eroded more slowly than the softer sand/ash matrix. The result is a wonderland of hoodoo gardens that are especially obvious along the edges of the many washes that criss-cross the basin. Some of these drainages such as Ah Shi Sle Pah, Hunter and Alamo–the two washes that formed the Bisti, and their tributaries have carved and exposed a treasure trove of unlikely works of earthen art.

The human history of the badlands is of course relatively short. Probably the most significant event in shaping the area in the last hundred years was the discovery of coal and the associated coal-bed methane. By the early 1980’s coal mining, mostly to fuel the nearby Four Corners Power Plant, was consuming large tracts of land throughout the basin. Inevitably, the Bisti became the center of a lawsuit between the Public Service Company of New Mexico and the Sierra Club; PNM already had a mining operation there and it looked like it might become just another large open-pit mine. However, the courts sided with the Sierra Club and in 1984, the Bisti was awarded wilderness status. In recent years, Ah Shi Sle Pah has also become a Wilderness Study Area. So, at least for the present, these gems are safe from the insatiable maw of “progress”.

Of the nine recognized badlands in the San Juan Basin, the Bisti is the largest–at 30,000 acres–and most well known. It includes the Kirtland and Fruitland geologic layers and was deposited 70-75 million years ago. The chief deposits are: sandstone, siltstone, shale, coal, and volcanic ash. Fossils include remains of T-Rex and large cypress-like conifers.

Ah Shi Sle Pah is much smaller than the Bisti, but was deposited around the same time, and thus contains the same geologic layers. It contains the same deposits: sandstone, siltstone, shale, coal, and volcanic ash. The fossils found in Ah Shi Sle Pah include remains of crocodiles, Pentaceratops (which has been found only in Ah Shi Sle Pah), early mammals, and of course, petrified wood.

The other recognized badlands in the basin are: Ojito–the oldest having been deposited 144-150 million years ago–, De Na Zin (70 -75 million years ago), Lybrook, Ceja Pelon, Penistaja (all 60-64 million years ago), San Jose (38-64 million years ago), and the youngest, Mesa de Cuba (38-54 million years ago).

The map shows the boundaries of the San Juan Basin. Rather than being formed by volcanism like the San Juan and Jemez Mountains to the north and east, the basin was uplifted as a single block after which the center collapsed to create the basin.

The idea for this post came from a show I had last year called Badlands Black and White. I chose to print all the images in B&W in order to focus on the graphic elements: tone, texture, patterns, etc.

This image was made in Alamo Wash in the Bisti Wilderness. The cracks that result from the shrinkage of the clay rich soil tell a story of the arid environment. The sandstone balanced on the short mudstone pillars is an example of the hardened sediment and how it weathers in relation to the softer layers below it.

The floor of most badlands is usually littered with small pieces of debris, which is comprised of bits that have broken or eroded from larger structures. They can be shale, clinkers (super-heated clay), siltstone, or even glacial deposits from the last ice age. There are often fossilized bone and clamshells mixed in with all or some of the above.

I made this image of a client while leading a tour in the Bisti Wilderness. The man is standing on an ridge above a deep wash in the Brown Hoodoos section of the wilderness. I wanted to give the viewer a sense of scale and the feeling of being lost in the bizarre surroundings.

These eroded pillars are in a small alcove located in a tributary of Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash. Some of them still have their sandstone caprocks, while some have lost theirs. The badlands are an evolving story of creation and degeneration, once the protective cover of the caprock is gone, the erosion process proceeds at a much faster pace.

This image is from Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash. The squat hoodoos in the foreground are relatively new and haven’t weathered out to the extent that some of the taller, more widely spaced ones have. Like many of the places I frequent in the badlands, I can’t visit this one without making several exposures.

At Ah Shi Sle Pah, there is a small, raised enclosure; I call it the Dragon’s Nest. What caught my eye the first time I saw it were the patterns and textures eroded into the solidified volcanic ash. This formation, at some time in the past, probably had a sandstone cap-rock.

I made this image in Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash. This collection of hoodoos sits in the middle of a labyrinthine tributary wash. The small column on the right has lost its caprock and is undergoing accelerated erosion.

This is a formation in the Bisti Wilderness that I call the Queen Bee. It is part of a small area of similar formations known as the Egg Garden. The cylindrical shape of these eroded forms is due to them being formed and hardened inside limestone tubes. As the surrounding layers eroded away, they emerged as distinct egg-shaped forms. The Egg Garden is one of the most popular attractions in the Bisti.

This small arch is another feature that brings people come from around the world to visit the Bisti Wilderness. The Bisti Arch can be deceiving; the opening is only about three feet across and half as high. The first time I found it, after searching unsuccessfully during previous visits, I was surprised by how small it is. The top of the arch is made of siltstone supported by a volcanic ash pedestal, and was once part of a wall which stretched across Alamo Wash.

In his book “Bisti” which was printed in the 1980’s, David Scheinbaum included an image of this formation with the caption: “This unstable hoodoo is just within the Sunbelt coal-mining lease and will probably be destroyed by mining in the near future.” I made this image on a recent trip to the Bisti Wilderness, and I’m happy to report that the unstable hoodoo is still standing.

Winter White (Balance)

The title of this post has nothing to do with color correction, or the temperature and tint of images. It has to do with the feeling that comes over me when I find myself enveloped in a cloud, surrounded by a world of white.

A good snow has become a rare thing here in the Jemez Mountains. So, it was a pleasure to wake up to nearly six inches of wet, white stuff recently. I dug my snow boots out of the back of my closet and ventured out into the white.

Growing things become dormant during the winter, but they are still an integral part of the landscape. I found these elongated clusters of seed pods and I was struck by both the contrast between and the similarity to the cottonwood trees in the background. The snow on the branches and on the ground served to intensify the graphic elements of the scene.

This scene of a snow covered bridge over the Jemez River needed only one element to make it complete: a human figure. Since I was the only one around, I volunteered myself. I set the timer on the shutter release and walked across the bridge.

These snow covered cholla cacti caught my eye; their prickly spines covered with a fresh coat of soft snow provided a conceptual as well as visual contrast.

The spring run-off usually happens in late April to mid-May. This is the earliest I have ever seen the river running this high and murky. I used a 3 stop neutral density filter to slow the shutter to 2.5 seconds in order to render the water as a smooth, chocolate colored flow with vanilla streaks. The background is lacking the rincon (a curved cliff face) which is normally visible from this vantage, but it is obscured by the low-hanging clouds.

The chiseled geology of Soda Dam is softened somewhat by the snow. There is never a lot of snow around it due to the warmth of the ground. Soda Dam is formed by a small warm spring that has laid down the calcium-carbonate deposit over thousands of years. The small waterfall was in deep shadow, so I made two exposures, one for the scene, and one for the waterfall. I then blended the two in Photoshop using a layer mask.

This final image was made in my driveway. I love the contrast of the trees against the nearly featureless, white…ish background. The normal view includes a ponderosa pine covered ridge.

By mid-afternoon, the world was back to normal, and most of the snow was melting. These ephemeral transformations are short-lived, but they serve to emphasize the things that I love about the place I chose to make my home.

The Creative Workflow (WYSIWYG)

I am constantly on the lookout for new images. Even while I’m driving, one eye is searching for a photograph. But, to really see, it is important that I be present so I can delve into the potential image, dissect it and study the relationships between the elements. What is the best way to do this? What should I look for as I move through this process?

The first step is to ask myself: What was it that drew me to this scene? Usually it was a singular object, or a play of light over the landscape. The Soaptree Yuccas, the sidelit patterns, and the subtle light on the sand dunes at White Sands National Monument were what grabbed my attention and led to this first image. Understanding my motivation made it easier realize what I want to say with the photograph.

Next I had to frame the scene in a way that would tell the story in the best way possible. I placed the closest yucca up front, but a little off center, leaving little doubt that it was the main subject of the image. This placement also allowed me to separate it from the others in the middle ground and avoid a confusing and static composition. My choices for the exposure had to be based on the dynamic range of the scene, which, In this case, was pretty wide considering the bright highlights on the sand in the distance, and the dark tonality in the shadows near sunset.

The first technical requirement was that I capture a broad dynamic range, so I made a bracketed series of exposures that covered the entire spectrum of tonalities in the scene. Even though I didn’t need to use all the different exposures, it’s better to have them and not need them than it is to need them and…well you know. The next requirement was that the depth of field be wide enough to have sharp details front to rear. Because of the low light level at the time of day I was shooting this, the fact that I was shooting at the lowest possible ISO–to achieve the best possible image quality, and the small aperture needed to get the depth of field I required, my shutter speed was relatively slow–1/10th of a second. That meant that I needed to shoot with my camera mounted on a tripod (something I usually do anyway). It’s easy to see from this cause and effect chain how my creative workflow was based not only on composition and design elements, but also included technical considerations.

The second image of Sandhill Cranes at Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge was made at twilight, that special time in the evening just after the sun set and the light is bouncing off the upper atmosphere. I was taken by the reflection of the colored sky and the reeds in the placid water of the foreground, and the transition from the smooth to the to the rough texture of the water, which created a layer-like effect because of the sudden change in color and texture. This layer is also where the action takes place: the cranes mingling, spreading their wings, foraging for dinner. There is then an abrupt transition to the golden reeds and the darker background before the final shift to the lighter tonality and magenta shades of the distant mountains and the sky.

I had my camera mounted on my tripod as usual, but I kept the bullhead swivel loose so I could easily pan to follow the movement of the birds. This image also relies on a wide depth of field to preserve sharpness in the details of all the layers mentioned above. I wanted to make the layering effect more obvious, so I boosted the saturation and contrast a little. Once again, the thought process kicks in and the decisions are made. The point of all this is to stress the importance of being involved in the making of an image. If you want a photograph to be yours, you need to put a little of yourself into it, and you need to be intentional throughout the process.

Two Birds

I killed two birds with one stone the other evening: I did some “blue hour” photography, and I made some panorama images. I have been wanting, for some time now, to get out and photograph the “blue hour”. For those of you who are unfamiliar with the term, it refers to the hour before sun-up or after sundown when the light from the setting sun is reflected in the upper atmosphere. The more common name for this time is twilight, and it is divided into three distinct phases: civil, nautical, and astronomical. The duration of twilight changes depending on the time of year, and the latitude from which it is being observed. The blue reference has to do with the color of the light which has a wonderful bluish cast to it and is diffuse without any harsh shadows. So, I finally made myself go out into the diminishing day and drive to the Rio Puerco Valley. The prospect was sweetened by the full moon which would be rising about half an hour after sunset.

I arrived at my destination two hours before moonrise and set about scouting the area for a good location to photograph the event. Since I am quite familiar with the place, it didn’t take me very long to find what I was looking for. I set up my camera on a tripod and began making test images to determine the correct exposure. As the sun went down and the light softened, I began taking several series of vertical photographs which would later be stitched together in Photoshop to create the final panorama. The first image was made about thirty minutes after sunset and about twenty minutes before moonrise.

The second photograph was actually made earlier than the first, but it was more of a test to get the feel for shooting the panorama and I didn’t expect to take it any further. After all, it’s full of cattle, which I consider to be a blight on the landscape. But, in the spirit of expanding my horizons (thank you Robin), I processed the image and, as it turned out, I liked it.

From the information I had gathered from The Photographer’s Ephemeris, I expected the full moon to rise somewhere between Cabezon Peak (the volcanic plug in the distance) and Cerro Cuate (the more prominent double peaked mount). But as the horizon began to brighten I was somewhat dismayed to discover that the moon was not where it was supposed to be…well at least not where I expected it to be. I checked the app on my iPhone again and saw that my expectations were based on a location that was actually a couple miles east of where I was.

I had planned to include the moon with the two mountains in the composition; that wasn’t possible from the place where I was standing. Now I had to re-think my plans, knowing that my window of opportunity was small if I was going to capture the moon close to the horizon. I quickly packed everything into my car and drove to the new location, walked to a place which afforded a clear view of the scene, set up, and composed the last image. By now it was dark, I was shooting thirty second exposures, and I was having to focus manually–auto focus doesn’t work very well in the dark. This being my first attempt at photographing at this time of day, and making panoramas, I wasn’t really very hopeful about the outcome. As full dark descended, I pack up my gear by the light of my headlamp and headed home.

The next morning I set about uploading and processing my previous night’s work. Each panorama is composed of nine vertical images which are then stitched together in Photoshop. As the first panorama was rendered I knew I was hooked. Somehow, despite the comedy of errors I had experienced while making the images, I managed to walk away with some finished photographs that I was happy with. It’s always an exhilarating feeling to discover a new technique and this was no exception. I made a few mistakes; there are some things I will do differently in the future, but overall, I’m happy with the way things turned out. It was a good night’s work.

Working With Light

Light can be a funny thing. One minute it’s soft, throwing just the right combination of highlights and shadows across a scene; then the sun comes out of the clouds, the light becomes harsh, and your scene becomes a hodgepodge of extreme contrast. While some photographers prefer harsh light for their landscapes, I have always looked for soft diffuse light in my landscape work. Perhaps my preference has something to do with my earlier close-up/macro work. Whatever the reason, I don’t care for a lot of edgy contrast in my photography.

In this image of lignite mounds and clinkers taken in the northern part of the Bisti Wilderness, the light is soft, but provides enough contrast to give shape to the features of the landscape.

If you think of your landscapes as portraits, which I do, this makes more sense. Any areas that are in deep shadow are hiding a part of the scene. Not only that, they are distracting and even extraneous. Crafting a fine landscape image can be much like writing an essay or novel: you have to finesse each element until it flows well with the rest of the composition. Of course there are times when you have to just accept the conditions you have and if you’re working in harsh light, you need to be aware of how to use the light to your advantage, and how to make adjustments later in post processing if necessary.

I made this image of rabbitbrush in a wash deep in the Bisti Wilderness. The light was harsh and I was shooting almost directly into it, but the wide dynamic range of my Nikon D 800 managed to capture all the information in one exposure. I was also able to make highlight and shadow adjustments in Lightroom during post processing.

This can be accomplished in several ways. Newer cameras are pretty good at capturing wide dynamic ranges within a photograph. Often, one exposure is enough to get all the information needed to produce a good final image. If you are unable to capture all the tones in the scene, you may need to make a series of bracketed exposures and combine them later in HDR software or by blending the exposures in Photoshop. There was time, not so long ago, when I shot five exposures for every image, and then blended them in Photomatix Pro. Now I try to get it all in one exposure. I only bracket exposures under extreme conditions.

Post processing software is becoming much better at making tonal corrections; the highlights and shadows sliders in Lightroom work wonders on a high contrast image. High ISO and low-light noise reduction are also much better in the newer cameras, and the ability of editing software to deal with these problems in post is advancing quickly. So, the tools are available, making good, even great, images under extreme lighting conditions is becoming easier, and the results look better than was possible just a couple years ago.

On a final note, I use Adobe Lightroom 5 and the latest version of Photoshop CC, but there are quite a few very good options out there. On One Software’s Perfect Photo Suite is just one example.

Check out more of my work on my website: http://www.jimcaffreyimages.com

Textural Fluency

Texture as a design element is often made to play second fiddle to some of its more obvious kin: line, color, even shape; but it can be a very effective tool in our bag of photographic tricks. It is important here to note the difference between tactile and visual texture. Tactile texture is what we feel when we touch a surface whether it be two dimensional–a piece of fabric, or three dimensional– a marble sculpture. Visual texture is the representation of a three dimensional surface in two dimensions. As photographers working within the confines of two dimensions, we are limited to the visual representation.

Everything has texture. It can be rough and aggressive, it can be smooth and subtle, or it can be somewhere in between. In this image the textures range from rough (the trees) to softer (the grasses) to softest (the low clouds). Texture can make an image more interesting by inviting the viewer to explore the interactions and relationships between the visual elements within the frame.

Textural differences add another design element to an image: contrast. The visual contrast in this image of cottonwood trees during a winter storm gives the viewer a reason to delve more deeply into the image; it attracts the eye and lets the person viewing the image know that I found the contrast between the low hanging clouds, the trees, and the grasses interesting enough to stop and make a photograph.

On another level, the repetitive, more aggressive texture of the trees in the photograph creates a pattern or motif which stands out and dominates the more subtle blending of the background clouds and foreground grass, so the trees become the focal point of the image. Finally, the different textures within the image create layers which add depth both visually and conceptually.

A Few Of My Favorite Things (Redux)

Here we are again (already) celebrating another year and renewing the circle. In looking back on 2014, I realize that I didn’t spend as much time in the field as I would have liked to. If I made resolutions, which I don’t, I would resolve to get out with my cameras more in the coming year. That being said, I did manage a few keepers over the past twelve months, so here they are.

Soda Dam is less than a quarter mile down the road from my home. It’s one of those places that is so familiar to me that I have a tendency to neglect it. I made this image on the last day of January.

Soda Dam is less than a quarter mile down the road from my home. It’s one of those places that is so familiar to me that I have a tendency to neglect it. I made this image on the last day of January.

The Rio Puerco Valley has been a great source of inspiration for me over the years, but I only made one trip there in 2014. It was well worth it; the atmosphere was putting on quite a show.

The Rio Puerco Valley has been a great source of inspiration for me over the years, but I only made one trip there in 2014. It was well worth it; the atmosphere was putting on quite a show.

In March I made a drive up to Abiquiu in search of nesting eagles. I didn’t see a one. But, I did find this scene of the Chama River just north of the village of Abiquiu. The light was amazing and the way it lit the distant peaks was icing on the cake.

In March I made a drive up to Abiquiu in search of nesting eagles. I didn’t see a one. But, I did find this scene of the Chama River just north of the village of Abiquiu. The light was amazing and the way it lit the distant peaks was icing on the cake.

Regina, New Mexico is a small village north of Cuba. It has a sleepy feel to it even though New Mexico highway 97 passes through the middle of the town. This old cottonwood, barn, and Chevy flatbed were watching what little traffic was moving by on the road. It seemed a bit nostalgic to me so I made this image.

Regina, New Mexico is a small village north of Cuba. It has a sleepy feel to it even though New Mexico highway 97 passes through the middle of the town. This old cottonwood, barn, and Chevy flatbed were watching what little traffic was moving by on the road. It seemed a bit nostalgic to me so I made this image.

In May I made several trips to the Bisti Wilderness, but I concentrated my efforts on the northern area off Hunter Wash instead of the more popular southern section off Alamo Wash. I found this nest of emerging hoodoos in a small hollow in the surrounding hills. The skyline is populated with small stone wings which are more prevalent in the north section than in the south.

In May I made several trips to the Bisti Wilderness, but I concentrated my efforts on the northern area off Hunter Wash instead of the more popular southern section off Alamo Wash. I found this nest of emerging hoodoos in a small hollow in the surrounding hills. The skyline is populated with small stone wings which are more prevalent in the north section than in the south.

A little further along on the same day I made this image of Robin making her way across the rolling bentonite hills near the highest point in the wilderness. When these soft hills erode, the incipient hoodoos buried beneath them will be revealed–as illustrated in the preceding photograph. The process is slow, but relentless.

A little further along on the same day I made this image of Robin making her way across the rolling bentonite hills near the highest point in the wilderness. When these soft hills erode, the incipient hoodoos buried beneath them will be revealed–as illustrated in the preceding photograph. The process is slow, but relentless.

In August we returned to the Bisti Wilderness on my birthday and I made this portrait of Robin and me on a small sandstone throne. We were actually within fifty yards of the highway which cuts through a rocky outcrop downstream from where Hunter and Alamo Wash converge.

In August we returned to the Bisti Wilderness on my birthday and I made this portrait of Robin and me on a small sandstone throne. We were actually within fifty yards of the highway which cuts through a rocky outcrop downstream from where Hunter and Alamo Wash converge.

This image is a bit of a cliché, but I think it does a pretty good job of telling the story: these places should not be taken lightly. The badlands of the San Juan Basin, or any wilderness for that matter, can be deadly. I never venture forth without enough water and a GPS receiver.

This image is a bit of a cliché, but I think it does a pretty good job of telling the story: these places should not be taken lightly. The badlands of the San Juan Basin, or any wilderness for that matter, can be deadly. I never venture forth without enough water and a GPS receiver.

When you shoot into the light as I did in this image, it is called contre-jour lighting. Actually this is not contra-jour in the strictest sense of the word; the sun was not directly behind the scene. But, the effect is pretty much the same. In this case, the backlighting lends a feeling of ephemeral mystery to the image.

When you shoot into the light as I did in this image, it is called contre-jour lighting. Actually this is not contra-jour in the strictest sense of the word; the sun was not directly behind the scene. But, the effect is pretty much the same. In this case, the backlighting lends a feeling of ephemeral mystery to the image.

This image was made one day after the previous one. In this case I was driving past a place that I see every day on the way home. I was struck by the intensity of the colors and by the uncertainty of the sky.

This image was made one day after the previous one. In this case I was driving past a place that I see every day on the way home. I was struck by the intensity of the colors and by the uncertainty of the sky.

The last two images were both made at Bosque del Apache NWR. The landscape is a view looking northeast along the south tour loop. It is a peaceful image and the colors are a bit of an emotional contrast.

The last two images were both made at Bosque del Apache NWR. The landscape is a view looking northeast along the south tour loop. It is a peaceful image and the colors are a bit of an emotional contrast.

This sandhill crane is displaying typical intensity as he takes wing from one of the ponds along highway 1 on the western edge of the refuge.

This sandhill crane is displaying typical intensity as he takes wing from one of the ponds along highway 1 on the western edge of the refuge.

I hope you enjoyed viewing my images as much as I enjoyed making them, and I wish you all a happy and healthy new year.

Finding Beauty

As photographers, it is our job to discover beauty in the commonplace, everyday subjects or interactions that we encounter. Usually, it is a challenge; rarely it is serendipitous. A change in the quality of the light, or a change in the relationship of the elements can make a dull, uninspiring view come to life. It is important that we remain vigilant or we will miss the fleeting opportunities that appear, seemingly, out of nowhere and then disappear just as suddenly.

I came upon this scene while driving the south loop at Bosque del Apache NWR. At first glance, I was not certain that it would make a compelling image, but the longer I studied it, the more potential I saw. The textural contrast was striking, and the color palette pleasing.

If you analyze the image, several things should be obvious: the reflection of the trees is somewhat blurred by the moving water, but there is still a feeling of quiet calm. The texture of the grasses and smaller trees add a subtle counterpoint to the tranquility, the color triad: blue, yellow, and red unify the composition, and the brooding sky lends a natural vignette to the scene.

Paying attention to these elements and emphasizing them during post-processing resulted in the image you see. Your interpretation of a scene and the way it looks in the final outcome, is subjective and is only limited by your own imagination and creativity.

Stepping Out Of Your Comfort Zone

It’s easy to fall into a rut. It’s not so easy to climb out of one. Often when we find a certain process, or visual framework that works for us, it becomes hard to move on from there. This kind of dependency works against the creative process by stifling our ability to see things in a new way. Sometimes the only way to escape this trap is to be intentional and to actively seek new answers, new ways of seeing or experiencing the world around us.

It matters little if you are famous or unknown, creative growth demands that you evolve. It is the natural order of things. If you find a niche in which you are comfortable, it is important that you keep exploring new ideas and processes, otherwise it is only a matter of time before your niche can become a prison from which escape will become harder and harder the longer you inhabit it.

So, how do we step out of our boxes? How do we change our habits to attain a new level of creativity? It can be as easy as changing a lens to work from a new angle of view, if your work is predominately wide landscapes, you may want to start doing close-up/macro work for a while. Experiment with black and white and learn what it takes to make a successful B&W image. By changing the way you think about and approach your work, you are, in effect, flexing your creative muscles, allowing the juices to flow, and opening new areas of exploration, thereby broadening your creative potential

I’m not saying that we need to totally discard the things that work for us, but we do need to keep the edge sharp. Like anything else in life, creativity suffers from narrow-mindedness. So, don’t be afraid to try something new or different. The results may surprise you.

Chasing The Glow

Photography is greek for painting with light. So, it follows that any kind of light should be fair game. Right? I have never been a shoot-into-the-light kind of guy, but sometimes all it takes is for a scene to jump out and dare me not to capture it. Such was the case with this image of Jemez Pueblo. The distant mesa and buttes were backlit by the evening sun and the cottonwoods in the middle-distance were glowing . The ephemeral balance this created was too good to pass up. What I am trying to say is that if you can successfully overcome your biases, you may find a powerful new way to express your creativity.

The second image is of a scene I pass every day as I drive home. But, on this particular day, the light was exceptional ; the atmospheric conditions created the perfect backdrop, the trees and grasses along the river were aglow and in full regalia. It was as if the entire landscape was shouting “Look at me, look at me”. An everyday, commonplace view had been transformed by the nuances of the light.

In both cases, I could easily have kept driving and missed the opportunity to make these photographs. It is at times such as these that I need to give myself a little shove, to overcome inertia and see what I can see. If I had not taken the time to capture these images under these conditions, the magic would have been lost and the same scenes would not have had the same impact the next time I saw them.

If you click on either of these images, you will be directed to my website. I am offering 20% off on all purchases from now through the end of the year. Just enter the code HOL14 (no spaces) at checkout.

A Separate Reality

It has been well documented that color steals the show when it comes to viewing a photograph. I have written about this previously, but as I have evolved as an artist, my ideas concerning visualization have also progressed. When you look at the two versions of the image below, what is the thing that grabs your attention? What is it that makes one version better or more visually pleasing to you? Do you have the same emotional response to both, or do they each evoke a different reaction?

I love the shade of green in the color photograph. All the variations of shading change subtly from one tone to the next, the trees in the background are almost an afterthought. It is a relatively peaceful image.

The second version is rendered in black and white. There is more tension between the elements because the background trees are no longer visually less dominant. Their repetitive verticality vies for attention with the more random shapes and lines in the False Hellebore in the foreground. The contrast in tonality is also more obvious in the second version, making the image more visually aggressive.

I don’t mean to say that the black and white image is more successful in portraying the feeling I had when I recorded the scene, I am just pointing out that each version places more emphasis on certain elements in the composition. The result is two separate realities (apologies to Carlos Castaneda) that convey two different emotional responses to the same subject.

Splendid Isolation

Jack London said: “You can’t wait for inspiration, you have to go after it with a stick!”. My stick is solitude, or more precisely, a place where solitude is possible. Usually I am with one or more companions, whether they be clients on a tour, or a like minded friend, but the main ingredient, the thing that makes it possible for me to fly off to a world of my own lies not in the absence of company, but rather in the absence of barriers.

If I make an image that portrays the illusion, I have accomplished my goal. In fact, there are times that a human figure is essential to complete the composition. An inanimate object can also serve to convey the feeling of isolation by providing something for the viewer to empathize with:

A weathered fence post in the midst of multi-colored badlands…

or a horse skull perched on the edge of a labyrinthine wash. These anchors add a sense of scale to the image, and allow the viewer to immerse herself in the “splendid isolation” of the environment.

Sanding The Stone

Telling a story about a place using images isn’t necessarily as straightforward as it may seem. There are many layers of information; some need to be added to, others subtracted from. In the case of the badlands of the San Juan Basin, the latter is the case.

The landscape itself is in fact formed by subtraction. It is eroded by the force of wind, and water over time. Things are not always as they appear. The tree trunk in the first image is no longer composed of wood; it has, over time, become transformed by minerals that replaced the dead organic matter, making it a petrified semblance of its former self.

This layered channel sandstone was infused with minerals which leeched into the ground making it harder than the surrounding matrix. As the accumulated sedimentation eroded, the harder stone was left exposed.

Much like the landscape, these photographs were created by removing some of the information, more specifically, the color. A black and white image presents the bare bones of the subject and allows the viewer to see the underlying structure.

Most of us are subconsciously influenced by colors. We make associations between colors and a certain emotion or mood, so removing the color eliminates the preconceived idea, which in turn leaves us free to experience an image in a more visceral way.

The badlands are a visual experience; the textures, shapes, and patterns inherent in the stone and clay are extraordinarily diverse. So, whether the image is one of more intimate proportions as in this photograph of a small alcove in Ah Shi Sle Pah, or of a grander scale like the image of the Bisti Arch shown below, the simplicity of the black and white image allows the landscape to stand on its own merits.

And while the yellows, reds, browns, greens and magentas which paint these amazing places with an astounding palette, play a role in telling the whole story, the absence of those colors conveys the essence of their austere beauty.

The Intentional Image

I am a photographer, I consider myself an artist. I don’t want to take pretty pictures. I strive to make moving images. A deep green reservoir and a late winter storm moving across distant mesas,

or a lone tree trapped in its winter slumber while light dances on a faraway butte, I had an emotional response to these encounters. As a photographer and an artist, I want to capture not just the way these things appear, but the way these things feel. For me, the making of an image does not stop after the shutter is released. I am not one of those photographers that proudly proclaim that they only strive to capture the image the way it was; total objectivity and nothing less.

Art is not objective. By its very nature, it must be more than that. The artist attempts to convey a certain feeling to those who view his work. This can only be achieved by making an image that is more than just a representation of a scene. To do this requires what some condescendingly call “manipulation”. I call it creating the image and I will make no apologies for that.

Imagine a watering hole miles from any village or human activity. Now imagine a bovine visitor that plods through the dry, cracked, yet still soft earth that lines the edges of the oasis. The sky is overcast and the light, while soft, still shapes the edges of the cracks and lends a beautiful glow to the surface of the moving water.

In order to make these things tangible within the constraints of a two dimensional photographic image, some work must be done beyond the framing, composition, and exposure that make up the original capture. There must be some intention to the final outcome

There are many circumstances where I am challenged to make an image that is different from those that came before. From an oft viewed roadside scene to a sudden ethereal display of atmospheric magnitude, the real challenge is not just to capture a technically acceptable representation of that scene or phenomena, or to use some cliche template to compose it, the challenge is to render it in a way that is unique to my vision.

By doing so, I hope to evoke some response to my work, to kindle in the viewer an appreciation of the world beyond the pavement where they may never have been, or where they may have been, but have never really seen.

In one of his contributions to Eliot Porter’s book “The Place No One Knew: Glen Canyon On The Colorado”, Frank Waters wrote: “We measure minutes, the river ignores millennia.” And, although he was referring to the Colorado River, we can still make the same statement about any river. They carve and shape the lands they flow through not judging or playing favorites, and at times they provide a striking contrast to the arid environment that borders their banks.

The Rio Chama is such a river. It makes its way through north-central New Mexico flowing past some remote, but memorable scenery along the journey to its confluence with the Rio Grande. If you throw in just the right amount of foreboding skies and ethereal light, the scene becomes magical. It is my job to capture that magic and to cause those who view my image to be drawn in by it, to wonder what may lie beyond that bend. I hope I have succeeded.

Horsein’ Around

What promised to be a day of amazing atmospheric conditions and light came with an unexpected bonus during a recent trip to the Rio Puerco Valley. Those of you who are familiar with my work know that this is one of my favorite locations.

We were looking for something a little different, but, after all, how often can you visit one place and expect to come up with something fresh? I made a turn onto a side road that I had driven past many times; it headed off across a low mesa toward the double peaked Cerro Cuate. Out of nowhere came a small herd of horses. We could see by their brands that they were not wild. Their gregarious nature confirmed it.

One horse in particular took to Robin and she was enchanted.

As we wandered around the fringes of the band, they went about their business. These three stuck together and moved a short distance away from the two more friendly members of the group. Although I am no expert on horses or their behavior, I’m pretty sure they are mares.

I was amazed by the relaxed, friendly demeanor of these gentle animals. They are obviously used to being around people. These two struck a familial pose for me.

With the volcanic neck of Cabezon as a backdrop, these two males (I didn’t get close enough to be able to tell if they are stallions or geldings) proceeded to play with each other as if they were showing off.

In all, we spent about forty-five minutes with our new-found friends working the horses as I would a model in a portrait shoot. I was looking for something as I photographed and when I saw this frame I realized that this was it.

Just Up (Or Down) The Road

I live in a wondrous place. The problem I have is that, being surrounded by beauty has made me a little thick-skinned; I guess you could say that I take it all for granted. So, I am putting my thoughts down in words accompanied by images, not so much to convince anyone else, but to remind myself.

Fenton Lake is a small (less than 40 acres) manmade lake which was formed by construction of an earthen dam on the Rio Cebolla. The Cebolla itself is not really a river by most standards; it is, at most, three feet wide along most of its length. But, here in New Mexico, it qualifies. I made this image on a dark day. I was standing amongst the cattails at the north end of the lake. The ridge line to the southeast burned during the Lake Fire in 2002.

One of the most recognizable and well known features in the Jemez Valley is Battleship Rock. It is composed of rhyolite and was formed when the volcano that shaped the present-day Jemez Mountains erupted for the final (hopefully) time, the ash and lava flowed into a box canyon; when it cooled the rock filled the canyon and as the softer earth eroded away, the monolith was left exposed.

Jemez Springs is a small village (population: 250) that lies in the heart of San Antonio Canyon–the canyon formed by the Jemez River. Not much has changed, visually anyway, since I first came here in 1977. This is a typical mid-week, January evening.

New Mexico Highway 4 runs through San Antonio Canyon for about thirty miles before climbing onto the flanks of the Valle Grande and continuing across the mountain to Los Alamos (yes that Los Alamos: home of the atomic bomb). This stretch of the highway is about five miles south of Jemez Springs.

In the early years of the last century, there was an extensive logging operation in the Jemez Mountains. The logging company used a train to haul the logs to a mill in Gilman. They bored two tunnels through the solid granite that transects the Guadalupe Box and when the logging declined, the tracks were replaced by a road–New Mexico SR 485–which provides access to the Santa Fe National Forest. Some may recognize the tunnels from the role they played in the film “3:10 To Yuma”

The Jemez River cuts through Soda Dam, a large, seven thousand year old calcium carbonate formation left behind by a small, unassuming hot-spring next to Highway 4. It is located about three hundred yards from my door and is a huge tourist attraction as well as being the swimming hole for local youngsters.

The second image provides a better view of the river flowing through the “dam”, and of the swimming hole; the kids jump from the sides into the plunge pool. When the New Mexico Highway Department blasted through the formation to improve Highway 4, the building process was interrupted, and the dam has been eroding since then.

Focal Lengths, F Stops, and Tripods, Oh My

This is a post about gear (particularly lenses) and why I chose it (them) to make a specific image. I teach a digital photography class at a nearby college and one of the things I cover in that class is the effect that the angle of view (the angle of coverage of the lens) can have on how the image is perceived by viewers. There are four categories: broad landscapes (wide angle), intimate landscapes (normal to short telephoto), compressed landscapes (mid-long telephotos) , and macro/close-ups (macro lens).

This image of a small wash full of water was made in the Rio Puerco Valley after a monsoon rain. It is an example of a broad landscape; the depth of the image from foreground to horizon is exaggerated. I used a wide angle zoom with an aperture of f 22 to give me the depth of field I needed to keep everything sharp.

Nikon D800, Nikkor 17-35mm f2.8 @ 17mm; 1/30sec, f22, ISO 100, tripod

I made this image in Blue Canyon on the Hopi Reservation in northern Arizona. It is an intimate landscape; the area covered, side to side and front to back, is relatively small compared to the broad landscape. There is a feeling of immediacy or closeness about the image, as if it could fit in your living room. I used a medium telephoto zoom set at an aperture of f 11.

Nikon D700, Nikkor 28-70mm f2.8 @ 35mm; 1/25sec, f11, ISO 100, tripod

Using a telephoto lens causes an image to compress, so distant objects seem closer. A telephoto lens does not exaggerate the depth of the image the way a wide angle lens does. Instead, it causes elements to flatten, making the distance from foreground to horizon appear shorter, and making the elements in between appear more closely grouped.

Nikon D700, Nikkor 80-200mm f2.8 @ 200mm; 1/25sec, f8, ISO 100, tripod

There is something about the the world that lies right at our feet that is compelling. Although it is normally common and quite ordinary, given a little attention and a skilled eye it can become extraordinary. This is the world of close-up or macro photography. There is no need to travel to exotic locales when there is an unending source of interesting subjects to be found in your own back yard.

Nikon D300, Nikkor 105mm f2.8 macro; 1/60sec, f8, ISO 200, tripod.

Eyes On The Stars

If you drive west from Socorro, New Mexico on US 60 about fifty miles, you will find yourself on the Plains Of San Augustin. The plains are about sixty miles long and ten to fifteen miles in width and were formed by Lake San Agustin during the last ice age. They lie between the San Mateo Mountains to the east and the Tularosa Mountains to the west. At first not much catches your eye, just flat grassland. But as you drive farther along, you begin seeing things that really don’t belong in the middle of a dry Pleistocene lake bed.

Scattered across the flat terrain are groupings of large dish antennae, the scene looks like something out of a science-fiction movie. In fact it was in a science-fiction movie. Much of the movie “Contact”, which was based on Carl Sagan’s book by the same name, was filmed at the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array. And while, in the movie, the main focus of the array was to search for extraterrestrial intelligence, that is not really what scientists at the VLA are engaged in. Instead, they use the antennae to investigate astronomical features of galaxies and stars. The array was instrumental in communicating with Voyager 2 as it flew by the planet Neptune, and much of what we know about black holes, quasars, pulsars, supernovas… is because of observations made at the VLA and other installations like it around the world.

The VLA consists of twenty-eight antennae which are each twenty-five meters in diameter; twenty seven of them are online and working while one goes to the maintenance shed for…well, maintenance. The rest are arrayed along three tracks that are configured in a Y shape with each leg of the Y being thirteen miles long. When the antennae are set in their widest array, they, collectively, constitute a dish which is twenty-two miles in diameter. The individual antennae can be rearranged to suit the needs of the scientists using them. It depends on where, in the universe, they want to look.

To move the massive dishes (each one weighs 203 metric tons), technicians use special trains with pivoting wheels. The trains move along a double rail that follows each leg of the Y to pre-set positions where the train is raised, the wheels pivoted, and the train lowered onto the side tracks, then the dish is placed onto piers and bolted down. The last step is to re-attach all the servo and data cables to make the dish operational. As one can imagine, setting up a new configuration is a time consuming task requiring several days to complete.

Once all the dishes are in their new locations, operators at the Array Operations Center located on the campus of the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology in Socorro set the dishes to the correct azimuth and altitude so the scientists can make the observations they need.

The sight of these immense dishes spread across the plain, all looking in the same direction leaves me spellbound every time I see it. I am reminded of the vastness of the universe and of our place in it. The VLA site is a little off the beaten path, but it’s well worth the trip for anyone who looks up at the stars and wonders.

My Few Of My Favorite Things

Wow! Another year fades into memory. I have spent the last couple weeks editing the images I’ve made in 2013 with the goal of culling my favorite dozen. Image editing for me is a labor of love; I have a connection to my work, so picking “the best” out of hundreds candidates is not an easy task.

I knew from the time I made this photo of a bull elk in my yard on January 3rd that I was setting a high standard for the rest of the year. Also, not only was it serendipitous, but the image was a departure from my usual wide angle landscapes. I had been feeling for some time that my work had been stagnating, so I resolved then and there to take it in a new direction.

In early February, I ventured into an area along US 550 that I had been looking at as a shooting location for some time. I was drawn by some red sandstone pinnacles that were visible from the highway. As I walked toward them, I came across this old section of road that is slowly eroding, being reclaimed by natural forces. The scene made me realize how impermanent our impact on nature really is. In the end, this is the image that stood out above the others I made that day. Again: serendipity.

As the year progressed, I found myself revisiting some places I had been before. The image of the church on San Ildefonso Pueblo (a scene I had driven past countless times before) is more about the light than the subject matter. It is also a more visually compressed image than is usual for me due to my use of a longer focal length lens.

Every year at the end of May–Memorial Day Weekend to be exact–the Pueblo of Jemez hosts the Starfeather Pow Wow. Hundreds of native dancers from across the country come to dance and compete. I made hundreds of images that weekend, but this portrait of two brothers stood out. They are dressed in “dog soldier” head-dresses, hair-pipe breastplates, and feather bustles, all made by their father. Just before I released the shutter, I told them to give me some attitude. I think they did a pretty good job.

Anyone who is familiar with my work, knows that I spend a great deal of time in the Rio Puerco Valley. It was near the middle of July and the rains had just started after several months of searing heat and cloudless skies when I made this image. There are many possible causes for this animal’s demise, but the location of its desiccated remains along a now rain-filled wash and the rain falling from a heavy sky tells an ironic story about the uncertainty of life in this harsh environment.

And speaking of harsh environments, the Bisti Wilderness in July can be a sobering place. The temperatures can soar to well over 100°F. I usually try to discourage clients from booking a photo tour during this time, but if the monsoons have started, it can be relatively pleasant and the cloudy skies lend a sense of drama to the scene. I made this image of one of my clients pondering the maze in the Brown Hoodoos section of the wilderness.

From a land of parched earth to a place where water is omni-present; my travels took me to Wisconsin in August. On a day-trip to Olbricht Botanical Gardens with my daughter, I made this image of the Thai Pagoda. Normally I steer clear of this kind of symmetry in a photograph, but the structure, and the entire environment seemed to demand it.

Autumn is the best time to be in the badlands, especially if the atmosphere cooperates. Even though the ground was soft and the washes were running from the rain, there were still cracks in the earth. It was as though the soil had a memory of the scorching it normally receives and refused to let go. After processing this image, I realized that it was best to convert it to black and white.

During the months of September and October I spent a great deal of time photographing the trains of the Cumbres-Toltec narrow-gauge railroad which runs from Chama, New Mexico to Antonito, Colorado. I spent every weekend for nearly a month chasing the trains and the fall colors. In the end, my favorite image had nothing to do with color and everything to do with the train, the track and the trestle.

To most people, in the US anyway, November means thanksgiving. For me it is my annual trip to Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge. Over the years, I have come to relish my time with the cranes, herons, geese, and other waterfowl that call the Bosque home during the winter months. Even though I have thousands of images of the birds flying, taking wing, landing, wading, eating, and doing whatever else it is that they do, I still managed to make two of my favorites there in 2013.

This first is obvious and familiar: a crane in the process of taking off from one of the ponds to fly to the fields where he will spend the day foraging. The second is a departure from my normal Bosque images, but one that illustrates the reason that I keep returning year after year.

In December I travelled by train to visit my oldest daughter (an adventure I wrote about in my previous blog entry). Chicago’s Union Station was a surprise to me. I made several images inside the station and when I wandered out the doors to Canal Street, I found this scene. I was immediately drawn by the fact that while some of the elements had symmetry–there’s that word again–some didn’t. And of course the cherry-on-top: the wet pavement reflecting the lights and columns.

To B&W Or Not To B&W

What is it about a black and white image that fires our imagination? How does the removal of color from an image have such profound effect on what that image says to the person viewing it? In this post I am going to look at three of my photographs and discuss how the black and white versions differ from their color counter-parts.

This first image was made at Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash in New Mexico’s San Juan Basin. The gibbous moon was riding low in the sky and I captured its transit behind this rock formation. In the color version, while the moon is still center stage, it is overpowered by the strong contrast between the complimentary colors in the sky and the orangish brown rock.

In the black and white image, the moon regains its prominence; even though it is relatively small in the photo, the contrast between it and the dark sky gives it some visual weight in the frame. The foreground is suddenly more about the mudstone supporting the rock, again because of the lighter tones in that part of the image.

Another element that benefits from a black and white conversion is a textured pattern. This image of the cracked earth near the Eagle’s Nest in the Bisti Wilderness does pretty well in color, but when converted to black and white, the texture in the foreground becomes more prominent.

The image is suddenly more about the dry cracked earth which was my intent.

Sometimes it’s more about the overall feel of the image. This last photo of the Cumbres-Toltec was made as the train was crossing the bridge over the Chama River. I like the color version but the mood isn’t quite right. By converting the image to black and white and then adding a sepia split tone, I was able to pull the image together and give it a more somber voice.

There are many ways to accomplish a monotone conversion using Photoshop, Lightroom, or any of the other image editing applications that are available. The most important part of the process, I believe, is having the ability to control the tones as they relate to the colors in the original image. By using the B&W adjustment layer in Photoshop instead of a greyscale conversion (which dumps all of the color information), or the HSL sliders in Lightroom you can adjust these tones individually and your results will have more visual punch.

Train Tag

For the past month I have been learning to play the fascinating sport of train tag. It involves learning the route and the timetable of a certain train that runs between Antonito, Colorado and Chama, New Mexico. After becoming familiar with these elements, the next step is to drive from one point to another along the train’s route; the trick being to arrive at the next place in time to set up a shot before the subject arrives. After several weeks practice, I became pretty adept at getting to the good spots and making the images I wanted.

I made this image the first day I went up to try to get some fall photos of the train . It was mid September, way too early for fall color. I’m glad I went though, because it took several tries to get it right. The more I worked the scenes, the more intimate I became with the environment and the train’s schedule. As a landscape photographer, I rarely need to worry about time restraints, so this was a good experience for me.

The second image was made at the beginning of October. The leaves were just starting their transformation and I noticed that some of the trees were pretty dull, going almost immediately to brown. I’m not sure, but I think it has to do with the greater than usual scarcity of moisture we’ve been experiencing here in the southwest.

Fast forward another week and I finally found what I was looking for; the aspens had reached peak color. Even though some of them were still wearing green, I knew that this was probably the optimal time, so I had to make the best of it. This image shows the train making its way through an aspen grove about five miles north of Chama.

Farther up the route, the color was already gone and the first snow was beginning to cover the ground. I figured the same would be true at the lower altitudes within a few days, so this had to be it. It was also the end of the season for the train so this definitely had to be it.

To finish things off I wanted to capture the train approaching its destination (in this case Chama), so I began looking around and with Robin’s help, managed to find this trestle about a half mile north of the station. We raced the train down through the canyon stopping to photograph at all the good vantages and then made a mad run for the road that brought us close to the trestle. We had to make it in time to run across the trestle ahead of the train to get the image I wanted, but it was well worth the effort.

As the train came closer, I chickened out and moved from the center of the tracks before I made this final image.

Water, Water Everywhere

I have lived in the desert southwest for nearly forty years. So, when I suddenly find myself in an environment where water is plentiful, I am taken a little by surprise at the seemingly extravagant abundance.

Such was the case when I recently travelled to Wisconsin to visit my daughter and her husband. We spent a great deal of time exploring the natural wonders in and around Madison where they live. While visiting Olbricht Gardens, I was especially impressed by the Thai Garden and Pavilion. There are several reflecting pools and a fountain which has a gravel bottom. The contrast between the smooth surface of the water and the rough texture of the gravel provides a nice touch to the image of the pavilion below.

The Thai Pavilion is constructed of plantation grown teak and finished with gold leaf. It was built in Thailand, then de-constructed, transported to Madison and re-constructed on-site by Thai craftsmen. There are no nails or screws in the entire structure.

Not to be outdone by a fountain, Lake Superior, the largest body of fresh water in the world, made a lasting impression on me. It covers over thirty two thousand, eight hundred square miles. We paddled twelve of those miles in kayaks while exploring the sea caves at Apostle Island National Lakeshore.

I made this image from my kayak while my daughter’s friend Karin was paddling through a sea stack about half way through the trip. Lauren and Prasanna, her husband, can be seen to the right of the stack. In the image below, Karin’s kayak rests on a remote beach where we stopped for lunch.

After lunch and a short break, we began the trip back. I made this image of my daughter and her husband paddling their kayak with Karin and the expanse of Lake Superior beyond them. I kept my camera in a water-proof bag, so each time I wanted to make a photograph, I had to take it out of the bag and then put it back in being careful not to drop it in the lake.

Below is one last image of Karin who is an experienced kayaker as she makes her way through the deep waters of the lake with Sand Island, one of twenty-two islands in the Apostle Islands archipelago, in the distance.