Quiet Places

There are undoubtedly many beautiful places in this world that are photogenic without really trying to be. We have all seen them hundreds of times: Tunnel View in Yosemite, Delicate Arch in Arches, The Mittens in Monument Valley…But there are also those places that don’t jump up and pound their chests demanding your attention. The quiet places that are just as beautiful and meaningful in their own unassuming way as the shiny crowd pleasers.

In Joshua Tree National Park there is a grove of these members of the yucca family. It is tucked away in an alcove just off a dirt road in the northwest section of the park. There I found this specimen growing against a wall of sandstone.

In Joshua Tree National Park there is a grove of these members of the yucca family. It is tucked away in an alcove just off a dirt road in the northwest section of the park. There I found this specimen growing against a wall of sandstone.

Nikon D810, Nikkor 24-120mm f4 @ 120mm, 1/5 sec, f16

When snow falls in the mountains where I live, I am compelled by the mystery of the shrouded landscape to go into it and make photographs. In this image it was the drooping, snow-laden branches and needles that attracted my attention.

When snow falls in the mountains where I live, I am compelled by the mystery of the shrouded landscape to go into it and make photographs. In this image it was the drooping, snow-laden branches and needles that attracted my attention.

Nikon Df, Nikkor 80-200mm f2.8 @ 200mm, 1/500 sec, f8

This series of cascades on the Guadalupe River is choked by granite boulders that made for a precarious scramble on this winter day. The ice covered granite was slick and placing the tripod was tricky, but the results were well worth it. This spot is a favorite of mine and I have returned to it many times; this image is one of the best out of many that I have made in this location.

This series of cascades on the Guadalupe River is choked by granite boulders that made for a precarious scramble on this winter day. The ice covered granite was slick and placing the tripod was tricky, but the results were well worth it. This spot is a favorite of mine and I have returned to it many times; this image is one of the best out of many that I have made in this location.

Nikon F3, Nikkor 35-70 mm f2.8 @35mm, 1 sec, f18, Fuji Velvia

The slot canyons of the Colorado Plateau are remarkable for their other-worldly beauty. This image is from Little Wildhorse Canyon in the San Rafael Swell, but it could have been made in any of the countless other slots that make up the labyrinthine drainage system of central Utah.

The slot canyons of the Colorado Plateau are remarkable for their other-worldly beauty. This image is from Little Wildhorse Canyon in the San Rafael Swell, but it could have been made in any of the countless other slots that make up the labyrinthine drainage system of central Utah.

Nikon D810, Nikkor 24-120mm f4 @ 35mm, 1 sec, f11

If you are interested in purchasing a print of one of the images in this post, just click on the image and you will be directed to that image’s page on my website.

The Other Badlands

The Bisti Wilderness is by far the most well known of the badlands in the San Juan Basin. It was the most popular when I was leading photography tours out there. But, there are numerous other places that qualify as badlands. This petrified tree trunk is located in the Fossil Forest, a small area south of the Bisti Wilderness. It sits on the edge of a ridge which is the only elevated ground for miles in any direction.

This petrified tree trunk is located in the Fossil Forest, a small area south of the Bisti Wilderness. It sits on the edge of a ridge which is the only elevated ground for miles in any direction.

Nikon D700, Nikkor 16-35mm f4 @ 24mm, 1/25 sec, f16 While exploring a remote area along Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash several miles west of what is considered to be the Ah Shi Sle Pah badlands, I came across this curious formation in a small alcove near the edge of what I would describe as a sculpture garden of hoodoos.

While exploring a remote area along Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash several miles west of what is considered to be the Ah Shi Sle Pah badlands, I came across this curious formation in a small alcove near the edge of what I would describe as a sculpture garden of hoodoos.

Nikon D810, Nikkor 16-35mm f4 28mm, 1/40 sec, f18

Along the southern margin of Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash there is a zone which I think of as the yellow badlands. It is a particularly rugged area with steep drainages and many places that would easily collapse under a hiker’s weight into a subterranean maze of eroded caverns and channels.

Along the southern margin of Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash there is a zone which I think of as the yellow badlands. It is a particularly rugged area with steep drainages and many places that would easily collapse under a hiker’s weight into a subterranean maze of eroded caverns and channels.

Nikon D800, Nikkor 24-120 mm f4 @24mm, 1/5 sec, f18

This is another bizarre formation I came across quite by accident while wandering along the far western end of Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash. Since then it has become a destination. I’m happy to have known it before the masses arrived.

This is another bizarre formation I came across quite by accident while wandering along the far western end of Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash. Since then it has become a destination. I’m happy to have known it before the masses arrived.

Nikon D800, Nikkor 16-35mm f4 @32 mm, 1/15 sec, f16

If you are interested in purchasing a print of one of the images in this post, just click on the image and you will be directed to that image’s page on my website.

Adobe

Just about anywhere you go in New Mexico, you will find crumbling adobe ruins. They speak of a time when the pace of life was more relaxed, more sane. I have photographed hundreds of these ruins over the years. These are just a few of my favorites.

I have photographed this adobe wall several times. It is tucked away in a small northern New Mexico village. I love the layers on this wall, the peeling paint, the crumbling stucco, the eroded adobe, and then there’s the weathered wooden slats and peeling plywood.

I have photographed this adobe wall several times. It is tucked away in a small northern New Mexico village. I love the layers on this wall, the peeling paint, the crumbling stucco, the eroded adobe, and then there’s the weathered wooden slats and peeling plywood.

Nikon DF, Nikkor 24-70 f2.8 @42mm, 1/500 sec, f8

This rock/adobe house is tucked away in a village not far from where I live. I’ve driven past it thousands of times, but I never noticed it (hidden back off the road as it is). When I did finally see it it had a visual impact on me and I made this image.

This rock/adobe house is tucked away in a village not far from where I live. I’ve driven past it thousands of times, but I never noticed it (hidden back off the road as it is). When I did finally see it it had a visual impact on me and I made this image.

Nikon DF, Nikkor 80-200 f2.8 @150mm, 1/80 sec, f10

In eastern New Mexico there are many small communities that are just hanging on. They boomed during the 50s and 60s when many people were driving the Mother Road, US 66. Today they are but ghosts of their former selves. I found this old pink adobe in one of those villages.

In eastern New Mexico there are many small communities that are just hanging on. They boomed during the 50s and 60s when many people were driving the Mother Road, US 66. Today they are but ghosts of their former selves. I found this old pink adobe in one of those villages.

Nikon DfF, Nikkor 24-70 f2.8 @35mm, 1/640 sec., f10

I was attracted to the colors and textures in this scene. The house is located on a two lane highway in north-central New Mexico, but the small town was pretty much deserted

I was attracted to the colors and textures in this scene. The house is located on a two lane highway in north-central New Mexico, but the small town was pretty much deserted

Nikon DF, Nikkor 24-70 f2.8 @50mm, 1/160 sec, f5

If you are interested in purchasing a print of one of the images in this post, just click on the image and you will be directed to that image’s page on my website.

Rhododendrons in the Redwoods

The splendid rhodora now sets the swamps on fire with its masses of rich color. It is one of the first flowers to catch the eye at a distance in masses,–so naked, unconcealed by its own leaves.

Henry David Thoreau

Journal-May 17, 1854

I was lucky to be driving through the coatsal redwoods in northern California a couple years ago just at the time the rhododendrons were in bloom. Me being a desert rat from New Mexico, it felt like I was in a fairyland.

I was lucky to be driving through the coatsal redwoods in northern California a couple years ago just at the time the rhododendrons were in bloom. Me being a desert rat from New Mexico, it felt like I was in a fairyland.

The soft, fragile leaves and flowers of the rhododendrons set against the backdrop of the towering, solid trunks of the redwoods was a powerful visual element. The light mist in the deeper parts of the forest added to the sense of mystery in the scene.

The soft, fragile leaves and flowers of the rhododendrons set against the backdrop of the towering, solid trunks of the redwoods was a powerful visual element. The light mist in the deeper parts of the forest added to the sense of mystery in the scene.

If you are interested in purchasing a print of one of the images in this post, just click on the image and you will be directed to that image’s page on my website.

Herons!

I admire herons, they are solitary hunters, they mostly keep to themselves, and they are are quick to depart when something, or someone encroaches on their space.

I was photographing in the Bolsa Chica Wildlife Refuge near Huntington Beach, California when I saw this great blue perched atop a snag at a considerable distance from me. I grabbed my 600 mm lens and made several photographs. I like the way his guard feathers are moving as he turned his head

I was photographing in the Bolsa Chica Wildlife Refuge near Huntington Beach, California when I saw this great blue perched atop a snag at a considerable distance from me. I grabbed my 600 mm lens and made several photographs. I like the way his guard feathers are moving as he turned his head

This small pond at Bosque del Apache is usually crowded with cormorants, but on this day there was just this great blue heron hunting for a meal. It was a calm day, so there were hardly any ripples on the pond, which meant near perfect reflections. I stayed for a long time making photographs and this one was the best.

This small pond at Bosque del Apache is usually crowded with cormorants, but on this day there was just this great blue heron hunting for a meal. It was a calm day, so there were hardly any ripples on the pond, which meant near perfect reflections. I stayed for a long time making photographs and this one was the best.

This heron was perched along the edge of a dranage canal at Bosque del Apache in late December. It was a cold day and he was huddled against the frigid wind.

This heron was perched along the edge of a dranage canal at Bosque del Apache in late December. It was a cold day and he was huddled against the frigid wind.

I mentioned earlier that herons are usually pretty skittish and fly off if you try to approach them, but I’ve rarely had that happen at Bosque del Apache. It’s as if they know they are in a safe environment.

I mentioned earlier that herons are usually pretty skittish and fly off if you try to approach them, but I’ve rarely had that happen at Bosque del Apache. It’s as if they know they are in a safe environment.

These last two images are part of a series made over more than an hour while I watched this great blue heron hunting for his lunch. I made more than fifty photographs during that time, but these two tell the story pretty well I think.

These last two images are part of a series made over more than an hour while I watched this great blue heron hunting for his lunch. I made more than fifty photographs during that time, but these two tell the story pretty well I think.

Breathing the Light

There are times when the atmosphere puts on a show that, combined with the right light, cannot be ignored. If you happen to be in a place that provides a suitable setting for such a show, you may be able to capture it all in a way that reveals the power and beauty that nature paints under these conditions.

I made this image in 2007. I was in Canyonlands at Grandview Point when I noticed the storm moving across the buttes and mesas to the south and west. The ethereal nature of the light through the clouds and the haze of the falling rain was stunning. It took me a moment to realize that I should make a picture of this. If you look closely at the bottom right corner, you can see the Green River where it exits Labyrinthe Canyon at Hardscrabble Bottom. A few miles downstream is the confluence of the Green and the Colorado Rivers.

I made this image in 2007. I was in Canyonlands at Grandview Point when I noticed the storm moving across the buttes and mesas to the south and west. The ethereal nature of the light through the clouds and the haze of the falling rain was stunning. It took me a moment to realize that I should make a picture of this. If you look closely at the bottom right corner, you can see the Green River where it exits Labyrinthe Canyon at Hardscrabble Bottom. A few miles downstream is the confluence of the Green and the Colorado Rivers.

A veil of clouds above the Valle Grande and The Missing Cabin obscures Redondo Peak. Winter scenes such as this are common in the high country of the Jemez Mountains.

A veil of clouds above the Valle Grande and The Missing Cabin obscures Redondo Peak. Winter scenes such as this are common in the high country of the Jemez Mountains.

I was driving to Las Cruces for a calendar shoot and decided to take the scenic route through Lake Valley. As the clouds lowered to obscure the tops of a small range of hills, I rounded a curve to find these Cottonwood trees still wearing their autumn colors standing out in an otherwise sere landscape.

I was driving to Las Cruces for a calendar shoot and decided to take the scenic route through Lake Valley. As the clouds lowered to obscure the tops of a small range of hills, I rounded a curve to find these Cottonwood trees still wearing their autumn colors standing out in an otherwise sere landscape.

I was leading a tour in the Bisti Wilderness in December and by the time we arrived at the Egg Garden, the clouds had moved in and dropped down low on the landscape. Looking to the southwest, I noticed the sun attempting to shine through the thick cover; the result was a number of beams which died in midair much like virga (falling rain that never reaches the ground). Of all the times I have been to this location, I never witnessed better light than this.

I was leading a tour in the Bisti Wilderness in December and by the time we arrived at the Egg Garden, the clouds had moved in and dropped down low on the landscape. Looking to the southwest, I noticed the sun attempting to shine through the thick cover; the result was a number of beams which died in midair much like virga (falling rain that never reaches the ground). Of all the times I have been to this location, I never witnessed better light than this.

The Jemez River bosque south of Jemez Springs nestles close to the base of the wall of Virgin Mesa. I made this image on a winter morning a few years ago. The low clouds were veiling the canyon wall and created a sense of mystery and helped to define the branches of the cottonwoods and willows that line the bosque in that part of the canyon.

The Jemez River bosque south of Jemez Springs nestles close to the base of the wall of Virgin Mesa. I made this image on a winter morning a few years ago. The low clouds were veiling the canyon wall and created a sense of mystery and helped to define the branches of the cottonwoods and willows that line the bosque in that part of the canyon.

House On Fire Ruin

A while back, I wrote a blog post about the Fallen Roof Ruin on Utah’s Cedar Mesa. I stumbled upon it while researching another, more well-known, ruin which is located close by.

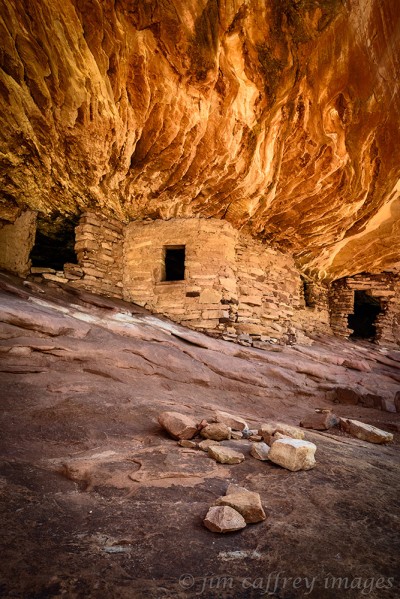

House On Fire Ruin is situated in the south fork of Mule Canyon which runs roughly parallel to Utah Rte. 95 about twenty miles west of Blanding. It gets its name from the way the alcove in which it is located lights up as it catches the reflection of the morning sun from the opposite canyon wall. When this happens, the texture in the ceiling of the alcove causes it to resemble flames coming from the top of the ruins. This phenomenon occurs mid-morning between 9 and 11 o’clock depending on the time of year.

This first image is pretty representative of most of the images I have seen made at the House On Fire Ruin. It does a good job of showing the ruin and the overall effect of the light reflection. But, I like to have a little more depth in my images, to tell more of the story of the place.

To do this, I simply backed off a little and changed to a portrait orientation to enable me to capture some foreground. This version seems less pinched to me than the first; it shows the floor of the alcove, which lends some context to the scene, and allows for some visual flow.

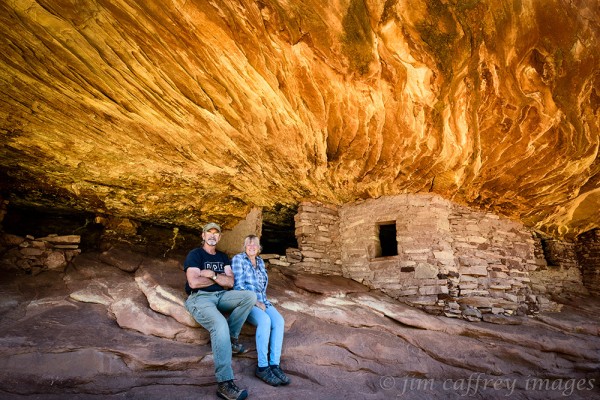

This final image is a portrait of Robin and me sitting in front of the ruins. I am always a little awestruck when I stand in a place where the ancients stood before me. This setting was even more powerful because of the interaction of the rock with the light. I wonder if the inhabitants of these ruins were as moved by the spectacle as we were.

These images were made in the fall of 2016. I had begun the draft, but, for some reason, never completed it. So, I am publishing it now, more than five years later. A lot of water under the proverbial bridge since then.

Relics of the Mother Road

Along the route and at road’s end, the decay of man’s dreams and the simple elegance of the natural scene have been the premier attraction. The pattern of dunes, the color of sheet metal, the weathering of wood, and the changing sky are images that are as important to me as the ‘grand view’.

John Kiewit; from the preface to Gone to Sanctuary from the Sins of Confusion

As I mentioned in a previous entry, I have been travelling around the state making images of a decaying way of life. A project and a journey inspired by a book. I wish I could have known John Kiewit, I think we would have had a lot to talk about..

Cuervo, New Mexico straddles what is now Interstate 40. In Cuervo’s heyday, it was Route 66. This deteriorating frame house is in the section of the town that sits on the south side of the freeway. I was drawn to make this photograph by what remains of the cedar shake shingles on the roof. As with most of the photographs I have made for this project, I shot the subject straight on. I think of these images as a hybrid of objective documentary and subjective, expressive photographs.

Cuervo, New Mexico straddles what is now Interstate 40. In Cuervo’s heyday, it was Route 66. This deteriorating frame house is in the section of the town that sits on the south side of the freeway. I was drawn to make this photograph by what remains of the cedar shake shingles on the roof. As with most of the photographs I have made for this project, I shot the subject straight on. I think of these images as a hybrid of objective documentary and subjective, expressive photographs.

The rusty, scavenged hulk of a car is as common in the rural New Mexican landscape as crumbling adobe. This one–I believe it’s from the 50s or early 60s– was parked near a small, completely abandoned village in Eastern New Mexico. There are many of these disappearing places and eroding vehicles along what was once “The Mother Road”.

The rusty, scavenged hulk of a car is as common in the rural New Mexican landscape as crumbling adobe. This one–I believe it’s from the 50s or early 60s– was parked near a small, completely abandoned village in Eastern New Mexico. There are many of these disappearing places and eroding vehicles along what was once “The Mother Road”.

I made this image in a small town that like many in that part of New Mexico is mostly a ghost town. The old picket and wire fence overgrown with weeds makes a perfect foreground for the faded pink wall and the glassless window. The rusted cans on the sill speak of former inhabitants, now long gone. I included just a little of the corrugated roof to provide contrast to the wall. As with most of my images, I made several versions, most of them wider views of the entire house, but I like the intimacy of this one.

I made this image in a small town that like many in that part of New Mexico is mostly a ghost town. The old picket and wire fence overgrown with weeds makes a perfect foreground for the faded pink wall and the glassless window. The rusted cans on the sill speak of former inhabitants, now long gone. I included just a little of the corrugated roof to provide contrast to the wall. As with most of my images, I made several versions, most of them wider views of the entire house, but I like the intimacy of this one.

I long ago outgrew the desire to use my camera as a Xerox machine. Standing amidst a throng of people with cameras on tripods to bag a “trophy shot” holds no attraction for me. That being said, when I saw a photograph by John Mulhouse of this quirky, timeworn truck parked in front of a now defunct resturant in Tucumcari, I knew I had to make my own photograph of it.

I long ago outgrew the desire to use my camera as a Xerox machine. Standing amidst a throng of people with cameras on tripods to bag a “trophy shot” holds no attraction for me. That being said, when I saw a photograph by John Mulhouse of this quirky, timeworn truck parked in front of a now defunct resturant in Tucumcari, I knew I had to make my own photograph of it.

I love the mottled look of the adobe on this house. The rusty corrugated tin roof creates tension. The curtained windows led me to suspect inhabitants, but there were no other signs of anyone living there. I wandered through this town for more than an hour and talked with one resident, but he confirmed that most of the residents were gone elsewhere.

I love the mottled look of the adobe on this house. The rusty corrugated tin roof creates tension. The curtained windows led me to suspect inhabitants, but there were no other signs of anyone living there. I wandered through this town for more than an hour and talked with one resident, but he confirmed that most of the residents were gone elsewhere.

This steel suspension bridge over the Rio Puerco no longer carries traffic. I can remember crossing it while on a road trip with my young family back in the eighties and, further back, I probably rode over it as a hitchhiker in the late sixties. Now it stands playing an uncertain role between the freeway and the frontage road. It’s been disignated a historic bridge and is on the national registry; the small, dented, rusting sign on the western end of the bridge tells us so.

This steel suspension bridge over the Rio Puerco no longer carries traffic. I can remember crossing it while on a road trip with my young family back in the eighties and, further back, I probably rode over it as a hitchhiker in the late sixties. Now it stands playing an uncertain role between the freeway and the frontage road. It’s been disignated a historic bridge and is on the national registry; the small, dented, rusting sign on the western end of the bridge tells us so.

Early spring and the elms and cottonwoods were leafing out. I was on a part of old route 66 that still has a few towns that are relatively well populated. As I drove through this village, I spotted this shuttered service garage. It is right on the main drag, but no one was around to fill me in on its history. I stayed there for a while because it felt like someone could walk out the door at any second. My patience was not rewarded.

Early spring and the elms and cottonwoods were leafing out. I was on a part of old route 66 that still has a few towns that are relatively well populated. As I drove through this village, I spotted this shuttered service garage. It is right on the main drag, but no one was around to fill me in on its history. I stayed there for a while because it felt like someone could walk out the door at any second. My patience was not rewarded.

This sunlight reflecting off the broken windshield drew my attention to this old rusty chevy. It was parked back off the road between two buildings. I had to wait for the sun to move so the glare was off the glass. There is something poetic about these old vehicles, something almost natural about the rust and the paint and the shattered glass.

This sunlight reflecting off the broken windshield drew my attention to this old rusty chevy. It was parked back off the road between two buildings. I had to wait for the sun to move so the glare was off the glass. There is something poetic about these old vehicles, something almost natural about the rust and the paint and the shattered glass.

I was actually back off the highway several miles when I came across this old adobe ruin. The vigas still sit on the walls, but the roof has long since given way to decay and gravity. It’s a small dwelling that harkens back to a time when quality was more important than quantity. It’s fortunate that I made this photograph in early spring; the elm tree was still pretty bare which, I think, suits the image.

I was actually back off the highway several miles when I came across this old adobe ruin. The vigas still sit on the walls, but the roof has long since given way to decay and gravity. It’s a small dwelling that harkens back to a time when quality was more important than quantity. It’s fortunate that I made this photograph in early spring; the elm tree was still pretty bare which, I think, suits the image.

Viva el Norte

The back roads of northern New Mexico are a treasure trove for a photographer willing to spend the time and energy driving from one remote village to another. I happen to live in one of those villages, so for me, it’s like visiting the neighbors.

I’ve discovered I have a thing for windows. More to the point, I have a thing for old windows in old walls. This first image required several trips before I got it right. I wanted to get the frame just so; the weathered log post plays an important part in the composition and the elevation proved to be tricky–I finally returned with a ladder in order to capture a satisfactory version of the photograph.

Nikon Df Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 F8 1/80 ISO 400

These adobe walls are about worn to the nub and the window frames, along with the viga used for a header, will eventually join the pile of rubble. As I drove past, I noticed how the windows were aligned and that is what drew me to make a photograph. The sage in the foreground also provides a nice anchor for the scene.

Nikon Df Nikkor 24-70 f2.8 F11 1/500 ISO 800

This scene literally jumped out at me as I rounded a curve in the road just south of Taos. I spent quite a while shooting from different angles, and when I edited the images, I chose this version because I like the spatial relationship between the tree and the mailbox.

Nikon Df Nikkor 24-70mm F8 1/400 ISO 400

I saw a photograph of this bar in a book titled Gone to Sanctuary From the Sins of Confusion that my friend Robin had loaned me. The book is a compilation by photographer John Kiewit who traveled the west for three decades from the late sixties through the late nineties making images of the places he saw along the way. The book was published in 1997 and, sadly, John died a few years later. But I was so taken by his work and the subject matter that I started driving to the places from the book which were relatively close to me. It became akin to a pilgrimage. Unfortunately, most of the locations have changed so drastically they are no longer worth photographing. This scene, however, was virtually unchanged from the image John made all those years ago. This one photograph made the entire quest worthwhile.

Nikon Df Nikkor 24-120mm f4 F8 1/640 ISO 400

I wish I could have visited this bar in it’s heyday, I’m willing to bet it was a pretty rowdy place, like something out of The Milagro Beanfield War–just my style. But now it sits abandoned, nothing more than a curiosity for passers-by and wandering photographers. Viva el Norte.

Nikon Df Nikkor 24-70mm F8 1/160 ISO 400

Those Crazy Pelicans

I have spent a great deal of time over the last ten years photographing cranes, herons, and geese at Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge. During that time, I have often thought of expanding my horizons to learn more about other birds, so I was delighted when the opportunity presented itself to photograph Brown Pelicans at La Jolla Cove near San Diego, California.

One of the first things that struck me about these ungainly creatures was their humorous behavior when they take a break from skimming the waves looking for dinner to rest on the bluffs along the shore. They can often be found in the company of cormorants and their interactions are sometimes pretty funny.

This one went through a series of gular gymnastics as a Double Breasted Cormorant looked on. The cormorant seemed unimpressed as the pelican turned himself nearly inside out.

Perhaps the most recognizable of the pelicans’ behavior is the stretching of their gular pouches in what has come to be termed the head toss. It’s not really a toss, but more of a steady extension of the neck until the bill is pointing straight up and the pouch is stretched. This is necessary to keep the pouch flexible and healthy. The trick in photographing this activity is catching a bird that is separate from all the others and in full view.

When you witness a head toss without knowing the reason behind it, you could be excused for believing these birds are a bit off kilter. Perhaps they’re howling at some unseen moon, or performing a weird pelican variation of the sun salutation.

Sleeping is a function that these birds perform with amusing inventiveness. The one-eye-open posture is one of my favorites. It’s as if they can’t quite trust that it’s safe for them to drift off. These two may have made a deal that they take turns napping and guarding each other.

And here is perhaps the most unique balancing act I witnessed over three days of watching these unpredictable creatures. He remained in this exact position for over an hour before standing to stretch his pouch.

One thing I have learned from all the time I have spent photographing birds is they are often synchronous in their movements and behavior, and pelicans are no different. These two were grooming on the bluff at La Jolla Cove. Even their feathers are in sync.

Four pelicans walk into a bar, one could care less, one thinks it’s all quite amusing, one is a bit embarrassed, and one is spoiling for a fight. Their antics endeared these birds to me. Watching them go about their daily routines had me smiling to myself almost constantly. I came away with a formative, but indelible image of these graceful, awkward, serious, comedic, eccentric birds.

Primal Earth

There are places in this world that defy expectations of how a landscape should look; places that are twisted and broken; places that are filled with other-worldly forms and shapes; and places that shift the spectrum of what we might think are normal hues for a landscape on planet earth.

Utah is certainly one of those places and in a small, overlooked area in the center of the state, where a layer of Mancos shale has been exposed by the elements, there lies an expanse of bluish colored earth, which depending on the light, might be a subtle grayish blue, or a more deeply saturated aqua-blue.

In every instance, the landscape is surprising; the texture can range from rough and deeply creased to smooth and almost sensual. In some places, it resembles a network of arteries (which, I suppose, in a way, it is).

In other places, it is a series of waves advancing on some forgotten beach. But everywhere there is at least a hint of blue. When you are used to red, sepia, or even more common grays and browns, the change can be quite startling. One location, in particular, was a prize we had to spend a little time searching for. Factory Bench overlooks what has come to be known as the Moonscape Overlook. It is a place that changes your perception of how the world should (or might) look.

If the light is right, the whole experience becomes exaggerated by the deep shadows playing over the complex terrain. Every twist and turn, every sinuous channel becomes more deeply etched into the unearthly earth.

Spending a night on the plateau above these badlands was an adventure in itself. A storm, which had been building throughout the day, moved in around sunset. Wind whipped the tent through the night and several times I was sure our shelter would be ripped away from us. But our little Coleman prevailed and by morning, things had calmed down enough that we could have a peaceful breakfast.

This last image was made looking east across the broken, variegated wilderness. Not far from here is the Mars Research Station where teams of scientists and engineers have been spending long periods of time in a simulated habitat to prepare for a possible trip to the red planet. The remote and other-worldly landscape allows them to make their preparations without light pollution or other outside influence.

On this same trip, we spent time in Capitol Reef and Goblin Valley. Probably it was the crowds and touristy nature of those parks that turned me off (I am a hopeless misanthrope), but neither of them had an impact on me as strong as did the blue badlands of Caineville Mesa and Factory Bench.

Fallen Roof Ruin

Sometimes a cherished memory starts with a rumor. I had heard of several ruins lying not quite forgotten in the serpentine canyons of Cedar Mesa in southeastern Utah. It was while researching one of them that I discovered another, less well known, but no less visually compelling.

Fallen Roof Ruin,which is actually a group of granaries, is located in Road Canyon which meanders in a, more or less, easterly direction from it’s head, in the heart of Cedar Mesa, to it’s final destination in Comb Wash. The single element that sets it apart from the numerous other ruins in Road Canyon is the staining in the roof of the alcove in which the ruin is located. A large section of the ceiling has fallen, leaving exposed white stains–most likely from minerals in the groundwater which leeched from the mesa top–that are painted across the newly exposed strata.

The hike to the ruin is just under two miles. The trail crosses the mesa top for about a half-mile before dropping over the edge into the upper reaches of Road Canyon. The descent is about one-hundred-fifty feet, and then the trail follows the canyon bottom pretty much staying in it’s watercourse. There is some rock-hopping involved along with some route-finding in the places where the trail leaves the drainage to make it’s way around some of the bigger boulders in the path.

I was not quite prepared for the impact of being in that place. There is something about the essence of these ruins that set them apart from other ruins I have visited. So, as is the case with all of my photography, I attempted to reveal at least a part of the soul of this extraordinary place through my compositions and processing. The large slabs of stone scattered across the floor of the alcove serve to tell some of the story; they are also useful as compositional elements in the images.

One of the most poignant pieces of this nearly thousand-year-old tableau is the presence of several hand pictographs above the entry to one of the small granaries. These were probably made by placing a hand on the stone and then blowing a powdered dye through a reed. Hand pictographs are common in the ruins of the desert southwest, and are thought to be a way of saying: “I was here”.

2015’s Best Part 2

As the title suggests, this is the second installment of my favorite images from 2015, and, as I mentioned in my previous post, the year was a departure for me in many ways. It is important for me as an artist to feel that my work is progressing. Last year I was able to move my work in new directions while exploring some new territory geographically as well.

As August gave way to September, I was eager to explore the Taos Plateau which I had photographed briefly while driving across it in August. At that time of year, the plateau becomes a sea of yellow due to the chamisa and snakeweed blossoms. The wildflowers, like the mountain asters in this image, accent the scene with bursts of color.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄25 sec., f16, ISO 32

The ultimate goal of this trip was the Rio Grande Gorge which cuts across the plateau to a depth of over a thousand feet. Most people see it from the Gorge Bridge west of Taos on US highway 64. But, there are many places along its length where you can drive to within walking distance.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄30 sec, f16, ISO 50

I tell the students in my Beginning Digital Photography class that you don’t need to drive to exotic places to make good photographs. Of course, it helps if you live in a beautiful place. I made this image of a mule deer buck in velvet in my yard. The blooming chamisa provided the perfect backdrop.

Nikon D300 with Nikkor 80-400 lens: 1⁄200 sec, f8, ISO 1250

In mid-September, we went to Kasha Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument which is located just south of Santa Fe where the Rio Grande finally exits the gorge after enduring the indignity of being impounded in Cochiti Lake. The hike to the top where the best views of the tent rocks are to be had passes through a narrow slot canyon which affords a cool respite from the late summer heat.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄320 sec., f13, ISO 800

My favorite images from that trip were these two of Robin in the slot. The second one became the title image for my show at the Jemez Fine Art Gallery: “The Path Less Travelled”.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄160 sec., f10, ISO 1250

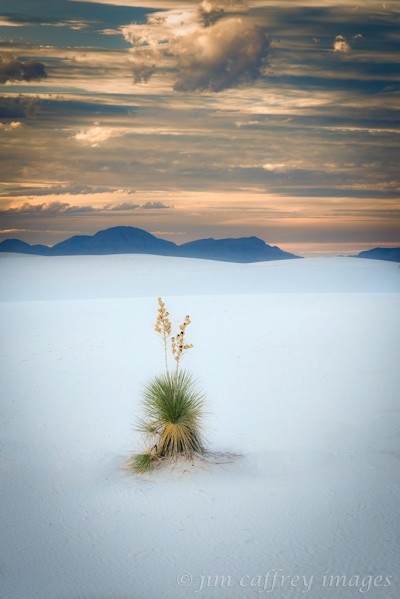

In September, we also made a trip to White Sands. As detailed in a previous post, the main reason for the trip was to photograph the White Sands Balloon Invitational, but Mother Nature had other plans. The lightshow at sundown was spectacular as this image attests.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-120mm f4 lens: 6 sec., f16, ISO 32

I love to break the rules. Dividing the frame in half is supposedly bad form, but with this image, I intentionally centered the top of the dune horizontally I think it works pretty well.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-120mm f4 lens: 1⁄8 sec., f16, ISO 32

The combination of the color and the peaceful quality of the dunes created a dreamlike atmosphere which I think I managed to capture pretty well with these last two images from White Sands.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-120mm f4 lens: 1.6 sec., f16, ISO 32

Both were captured near twilight; the intensity of the reds in the sky increased as the evening progressed. By reducing the clarity in Lightroom, I was able to enhance the dreamlike quality of both photographs.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-120mm f4 lens: 2.5 sec., f16, ISO 32

On the return trip from White Sands, we made a small detour to Three Rivers Petroglyph Site. There are over 21,000 petroglyphs on the rocks which cover the top of a ridge a little over a half mile long. Again, the weather cooperated and the light was perfect. This image of a hand petroglyph is my favorite from that shoot.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄15 sec., f16, ISO 32

In October, we made a journey to to southeastern Utah. The first night we camped at Goosenecks State Park and explored the surrounding area. In the Valley of the Gods, I saw this lone juniper tree perched on a rocky slope below a sandstone fin.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 16-35mm f4 lens: 1⁄15 sec., f16, ISO 32

On the second day, we drove up the Moki Dugway and then out to Muley Point. This was the surprise of the trip and we spent several hours climbing around the sandstone mounds that lie along the edge of the precipice overlooking the Goosenecks of the San Juan. In this image a small juniper clings precariously to its niche overlooking the serpentine canyons and the monoliths of Monument Valley on the horizon.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄8 sec., f16, ISO 32

Our ultimate destination was Monument Valley. It had been nearly forty years since I was last there, and while there were some changes: notably, the View Hotel, the prospect out over the valley and the sandstone buttes was unspoiled. We camped within view of the Mittens. I made this image of our campsite on our first evening there.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 133 sec., f16, ISO 32

John Ford Point was made famous by the director of the same name in his 1939 movie “Stagecoach”. I did make my own version of the iconic image: a native on horseback gazing into the distance from the point. But, my pick is this image of a rider moving away from the point while clouds hang low over the valley, partially obscuring the mittens.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-120mm f4 lens: 1⁄640 sec., f16, ISO 1600

As we were driving down into the valley on our first day there, I noticed this raven perched in a juniper right by the roadside. I moved slowly at first , not wanting to spook him before I could get the shot, but the more we photographed, the more I realized that he wasn’t going anywhere. As we packed back into the car, he began squawking. I think he was expecting a tip.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄10 sec., f16, ISO 32

This image is a replication of a photograph that Ansel Adams made in 1958. I don’t make a habit of shooting from other photographer’s tripod holes, in fact I will go out of my way to avoid doing so. But, hey, he’s Ansel Adams.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄20 sec., f16, ISO 32

When we pulled into the North Window parking area, I saw this dead juniper along the roadside and was immediately drawn to it. There is something about the bare bones of a twisted juniper tree in this landscape that just fits together.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄20 sec., f16, ISO 32

In November I travelled to Las Cruces to photograph a group of women for a Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math calendar. On the way I took a detour through Lake Valley and came across this stand of cottonwoods still in their autumn colors. I was attracted by the contrast between them and the drab landscape, and the low-hanging wintry sky.

Nikon D810 with Nikkor 24-120mm f4 lens: 1⁄4 sec., f16, ISO 32

2015’s Best Part 1

2015 was an exceptional year for me in terms of photography. Not just for the images, but for the experiences as well. I made an effort to be more adventurous, and spontaneous in my choice of subject matter. I also vowed to be more responsive to the images themselves when it came to post processing. In all, there are thirty-seven photographs, so I will present this post in two parts. I hope you enjoy viewing them as much as I enjoyed making them.

In late January we had a heavy snowfall which made it impossible for me to drive out of my driveway. So, I walked down to Soda Dam to photograph it in its winter splendor. This image seemed to be a black and white candidate from the start.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70 f2.8: 1.3 sec., f20, ISO 50

March took me to southern Arizona to photograph desert wildflowers. I didn’t find the showing I had hoped for, so I contented myself by pursuing Teddy Bear Chollas. When photographed in the right light, they have a luminous quality about them. I made this image at sunset in the Lost Dutchman State Park, east of Pheonix. The fabled Superstition Mountains lie on the horizon.

Nikon D800 with 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1.3 sec, f16, ISO 50

I’ve been to Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash many times over the years, but I seldom explore along the southern edge. In April I decided to change that; I made this image looking northwest from the top of the southern rim. This is the section I call the Yellow Badlands. It’s like taking a look back through time.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70 f2.8: 1⁄8 sec, f18, ISO 50

In May while exploring a part of Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash I had never been to before, I came across this incredible hoodoo hidden in a small ravine along the northern edge of the main wash. I stayed and worked the area for nearly two hours. This is the first of many compositions using what I call the Neural Hoodoo as the main subject.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 16-35mm f4 lens: 1⁄30 sec, f16, ISO 50

This black and white image was made from the opposite side of the Neural Hoodoo. If forced to choose a favorite, this would be it.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 16-35mm f4 lens: 1⁄25 sec, f16, ISO 50

This final image of the Neural Hoodoo was made from the same general location as the first, but I zoomed in to capture a more intimate portrait.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 16-35mm f4 lens: 1⁄15 sec, f16, ISO 50

At the same time I was exploring the far reaches of Ah Shi SlePah, I was discovering some of the amazing and convoluted drainages along the southern rim of the wash. I made this image on a stormy evening in late May. I could not have asked for more appropriate light for this scene.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄60 sec, f18, ISO 50

In early June I went out to the Bisti Wilderness. At the far reaches of the southern drainage, I made this image of a multi-colored grouping of hoodoos. I had photographed this same group several times in the past, but I think this is my favorite. The clouds seem to reflect the lines of the caprocks.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70 mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄40 sec, f16, ISO 50

One morning in late June I noticed the chollas around my house were blooming. I set out the next morning for the Rio Puerto Valley to capture the splashes of color in that dramatic landscape. I made the first image (above) in the ghost town of Guadalupe. The return of life to the desert seemed coincidental to the ongoing decay of the adobe buildings.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄6 sec, f16, ISO 50

In this image, a blossoming cholla stands at the head of a deep wash as a rain cloud passes over Cerro Cuate in the distance. Even the slightest precipitation sustains life in this environment.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄10 sec, f16, ISO 50

Early on the morning of July 4th, before the road was closed for the parade, I slipped out of town and drove out into the San Juan Basin. I didn’t really have a plan other than to visit the Burnham Badlands, which lies to the west of the Bisti Wilderness, and covers a relatively small area as badlands go (about one mile by two miles). This graceful hoodoo sits smack in the center of it.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄20 sec, f16, ISO 50

After completing my exploration of the Burnham Badlands, I drove west through the heart of the Navajo Reservation and arrived at Shiprock in the early evening. I drove one of the dirt roads that runs along the lava dike until I found a spot I liked. I set up my camera and tripod then waited for the light. Over the next two and a half hours, I made almost a hundred exposures as the light changed and the sun crept toward the horizon. This is my pick.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄6 sec, f16, ISO 50

Hidden in plain sight, just a few miles north of Ah Shi Sle Pah is the Fossil Forest. At the end of a low ridge which runs east to west, you can just make out the telltale signs from the county road: the striated color, and the deep cut drainages where geologic treasures lie exposed. I went there with an agenda: to find a fossilized tree stump. I’ve related the whole story in an earlier post, so I’ll just say here that we were able to locate the stump after some scrambling and sleuthing.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 16-35mm f4 lens: 1⁄25 sec, f16, ISO 100

In July, I made a trip to visit my daughter Lauren in Madison, Wisconsin. She accompanied me on the return trip. Early on the second morning, somewhere in central Kansas, she mentioned the large birds roosting on the fence. I had driven past and hadn’t noticed them, so I backtracked until we found them. The birds turned out to be a committee of turkey vultures sunning themselves and drying their wings. I was able to get pretty close to them without distressing them, and I managed to capture quite a few exposures. This is my favorite.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 24-120mm f4 lens: 1⁄640 sec, f9, ISO 500

In August we set out on the high road to Taos. The way passes through many small villages: Chimayo, Truchas, Las Trampas, and Picuris Pueblo to name but a few. At Picuris, we visited the plaza, and there, I noticed the shapes and texture of the adobe walls of a small church. This is the result of my efforts there.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 24-120mm f4 lens: 1⁄400 sec, f14, ISO 1600

Farther up the road, we took a fork to visit the village of Tres Ritos. There, in a meadow by the side of the road, was a spray of mountain asters with a small wetland full of cattails just beyond it. The dark foreboding sky intensified the saturation of the colors and was the perfect backdrop for the scene.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄640 sec, f16, ISO 1600

In late August on a trip to Denver, I drove up highway 285 instead of using the interstate. Late in the day, the clouds were hanging in tatters from the peaks of the Sangre de Cristos to the east. The grasses were just beginning to turn and the colors filled the spectrum. When I came across the trees, it all came together.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄5 sec, f11, ISO 50

On my return from Denver, I was driving across the Taos Plateau and the nearly full moon was climbing through the clouds above the Sangres. The Chamisa was in bloom and all I needed to do was find the right combination.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 80-200mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄500 sec, f13, ISO 800

Still on the Taos Plateau. The texture and colors in the grasses and sage, along with the rays of sunlight piercing the dark clouds caused me to pull over again (at this rate, I would never get home). The lonesome Ponderosa Pine anchors this image, but the thing that really ties it all together is the thin strip of light colored ground below the mountains.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 80-200mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄500 sec, f11, ISO 800

Monument Valley

From the north, you can see it coming from a long way off. The spires and monoliths peek above the horizon to give you a preview of the awe inspiring landscape you are about to encounter. Monument Valley: the quintessential western landscape.

From the campground located near the entrance to the valley, the well known Mittens and Merrick Butte are front and center. As we made camp, my attention was continuously drawn to the expansive landscape; I felt like I had fallen into an old TV western.

One hundred and ninety million years ago this area was covered by sand dunes much the same as the Great Sand Dunes in south-eastern Colorado. Over the intervening time, the dunes were compressed, hardened, and finally eroded until they formed the sandstone buttes, mesas, and pinnacles we see today.

The landscape here is unique. Perhaps not geologically, but visually it is different from any where else on earth. And, it is recognizable due to its connection to the movie industry. So, making images of the valley that are fresh can be a challenge.

The atmospheric conditions that prevailed throughout our trip ensured some dramatic, and at times forboding, skies. The low hanging clouds shrouded the monoliths and helped lend a bit of mystery to an already awe inspiring landscape.

One of the best ways to assure that your images are different is to move away from the proscribed “scenic views”. For this image I made of the North Window, I walked away from the area where all the photographers were and found this weather beaten, dead juniper by the side of the road.

But sometimes, you just need to go with the flow and make a photograph that’s been made a thousand times before. This is one of several photographs I made at John Ford’s Point. The first one showing a horse and rider moving away from the point under low clouds is more spontaneous.

It seems that everywhere you look there is a photograph to be made. The expansive views, the weathered junipers, and the unique rock formations are an image maker’s dream come true. It is no wonder this place has become a mecca for film makers and photographers.

Ansel Adams was one of my very early inspirations to become a photographer. In 1957 he made an image in Monument Valley and I could not resist the chance to pay homage to the man by making my own version. Standing there and seeing this same view that he recorded all those years ago was a moving experience for me.

There are times when everything just seems to come together; serendipity is a beautiful thing. When I noticed the raven perched in the juniper with the West Mitten as a backdrop, I rushed to get into position to capture the moment. Luckily, the bird seemed to be in no hurry to leave his perch and I was able to work the scene until I found the right composition.

This trip is now a fond memory, but I know I will be returning soon to this magical place where time (and the birds) stand still.

Mexican Hat Dance

A recent rip to Monument Valley yielded an unexpected, but memorable side-trip. While researching places to camp on the trip, I came across Goosenecks State Park near Mexican Hat, Utah. It’s only twenty-five miles from Monument Valley, and it’s right next to Valley of the Gods. What better place to use as a base camp?

The thing about the Goosenecks is, it’s hard to capture an image that shows the true complexity of the twists and turns the river takes as it flows through this stretch. Maybe a drone next time. Nonetheless, we set up our camp right near the edge of the gorge. As we got in the car to leave for Valley of the Gods, the wind began picking up, so, not wanting to come back to find our tent had blown into the chasm, we collapsed it and weighted it down with rocks.

I took less than thirty minutes to reach Valley of the Gods from our campsite. As we entered the valley, we were nervously eyeing the heavy rain that was moving across the southern horizon. The sky was black and the features of the landscape were obliterated by the walls of falling rain. The dirt road that runs through the Valley of the Gods is seventeen miles long and the last thing we wanted was to get stuck in the middle of it in a downpour. The soil has a high clay content which means that, when wet, the roads quickly become impassable. But, as we drove into that beautiful landscape, our worries about the weather vanished and were replaced by awe inspiring views.

As it turned out, we made the drive without incident, and when we returned to camp, the sky had cleared enough to give us a nice view of the waxing crescent moon. The next morning, I was up before dawn, we made breakfast, struck camp, and were on the road soon after. The destination for the day: Muley Point via the Moki Dugway.

The Moki Dugway is a road carved into the side of Cedar Mesa. It was made in the 1950s by a mining company as a way to transport uranium ore from the mine to the mill near Mexican Hat. It climbs over twelve hundred feet in a little under three miles by a series of switchbacks. As we drove the road, we saw a rusted hulk lying on a bench about a hundred feet below, someone missed a turn. About half way up the route, there is a turn out and we stopped to make some photos before continuing on to the top.

The first thing you notice when you reach Muley Point is the expansive view; looking south the incredible complexity of the Goosenecks of the San Juan River is front and center, and the sandstone monoliths of Monument Valley are visible on the far horizon. We began to explore the terrain along the edge of Cedar Mesa and were rewarded with some breathtaking vistas. I made lots of images, it seemed that around every turn there was something worth capturing.

I was on a natural high the whole time we spent at Muley Point, and looking at these images on my monitor at home still gives me that feeling: grounded, yet chaotic, like the landscape. The next time I go I plan to camp right there so I can explore in a more leisurely fashion.

Each of these images was made from a different perspective, and although they are essentially of the same place, they each tell a different story about how it all fits in the broader landscape. There is no shortage of great foreground elements at Muley Point, but beyond that the serpentine canyons cut by the San Juan River and the tributary ravines like Johns Canyon put on a show that changes constantly with the light.

I was reluctant to leave Muley Point, but I promised myself that I would return soon. So, we packed up and drove back down the Moki Dugway and past Valley of the Gods, southbound toward our ultimate destination: Monument Valley.

An Ancient Canvas

On the way home after our last trip to White Sands, which I wrote about in my previous post, we stopped at Three Rivers Petroglyph Site. Three Rivers is located about sixteen miles north of Tularosa, New Mexico, and is administered by the BLM. It has one of the largest concentrations of rock art in the American Southwest–more than twenty-one thousand glyphs.

The petroglyphs were made by a now extinct culture, the Jornada Mogollon, who inhabited the area from 900-1400CE. They are the same people who lived at the more well known Gila Cliff Dwellings located about two hundred miles west. I always feel a connection when I see evidence of these ancient people’s existence. I imagine them there in the dim past, standing in this same spot and creating their art.

Many of the petroglyphs at Three Rivers can be seen along the one mile trail which follows a basalt ridge. The artists used stone tools to carve their works into the dark patina covering the rocks; and in some places, nearly every square inch of available “canvas” is covered with drawings.

Visiting such a place makes me realize that, as an artist, I am a member of a long line of humanity that has felt the need to express their interpretation of things or events which defined their lives. Were these artists-of-their-day respected members of the clan? Were they rebels? Did they rail against social injustice?

The real significance of these works, aside from recounting the lives of a long lost culture, is their ability to connect us, as people, across the chasm of time.

Finding The Fossils In The Fossil Forest

In my previous post: Roaming The San Juan Basin, I described a two-day journey through a place with landscapes as varied as they are timeless. At one point during that journey, I passed a nondescript cattle guard on San Juan County Road 7650. To the north, a little more than a mile from the road is a ridge that has been eroded over time, and which now displays all the telltale signs of a badlands: deeply eroded gullies with unevenly spaced bands of color, large areas of red deposits, and the unmistakeable outlines of hoodoos against the smoother walls of hardened ash and clay. I filed it away for future reference.

Actually I had been aware of this small badlands for several years, but had never explored it. I decided to make the effort in the near future. So, a few weeks later, Robin and I loaded up the car and headed out to the Fossil Forest. At the top of my list was finding a certain petrified tree stump that overlooked a drainage to the south. I had found a photo of the stump online and had a copy of the image on my phone; as it turned out, it was an invaluable aid in ultimately finding the location of the fossil.

The view from the ridge top across the clay mounds, and ravines to the wide expanse of the San Juan Basin

From the parking area on the road we walked about a mile to the north until we reached the small drainages and scattered hoodoos that marked the boundaries of the badlands. We then explored some of the drainages to see if there was an obvious, or easy way to the top. No such luck. Eventually, we came across a relatively wide ravine near the eastern edge of the ridge. I recognized a petrified log I had seen on the BLM website; it was partially buried and lying near the mouth of the the wash. This seemed like a good place to begin the climb to the ridge top.

Actually, it was more of a scramble than a climb. There is about a one hundred foot elevation gain from the mouth of the drainage to the crown of the ridge, but it was steep. Once on top, we surveyed the area from our new perspective. To the east lay a jumble of clay hills with bands of black (lignite) and daubs of red (clinkers). To the north and south were more banded hills that fell away into the steep sided ravines which emptied onto the desert floor.

Now that we were on top, we began looking for the features that were visible in the photo I had on my phone. We came across several petrified logs most of which were eroded and broken into small pieces. At each of the promontories that intersperse the ravines, I walked to the point to compare the features. It was after several failed attempts that I looked across the next channel and spotted the stump.

There is a feeling of accomplishment that comes after searching for and finding something that is situated in a remote location, especially if that something is a millions year old relic of a former time. As I made these images, I tried to imagine the way the world was when this remnant of a lost age was intact and alive. It is not unlike the emotion I experience when I stand among ruins that were constructed by unknown hands thousands of years ago.

We spent a half hour or more working the scene from different perspectives before deciding to begin the hike back to the road, the car, the present world. After negotiating the way down from the crest of the ridge, we followed one of the many washes that empty into a series of small arroyos that drain this part of the San Juan Basin. On the way, we passed a mound of mudstone and lignite that was just beginning to reveal its secrets: yet to be formed hoodoos, still uncovered petrified trees, possibly the petrified bones of an, as yet, undiscovered dinosaur. What will this landscape look like a hundred thousand years from now? Will there be anyone around to wonder at its past?

Roaming The San Juan Basin-Part 2

My previous post: Roaming The San Juan Basin-Part 1, was about the first day of a two-day road trip through the expanse of a great bowl shaped depression in the middle of the Colorado Plateau in northwest New Mexico. I spent Saturday night in Farmington and awoke early on Sunday. I had planned to head straight home from there, but as I prepared to leave, I thought better of it and decided to do some more exploring. As I drove up the road that leads from Farmington to the edge of the basin, I began to formulate a plan. I decided that I would avoid any of my normal haunts: the Bisti Wilderness, Ah Shi Sle Pah, etc. and that I would try to stay on dirt or gravel roads as much as possible. With this blog post in mind, I also decided to take a photojournalistic approach to making my images as opposed to my usual process.

I left the paved road about forty miles south of Farmington and immersed myself in the rolling, broken landscape. The San Juan Basin has numerous drainages of all sizes that carve the washes and valleys that form the irregular surface and expose the long buried geological features. I turned south on a road I knew would take me past Ah Shi Sle Pah…forbidden territory on this trip. I noticed three abandoned dwellings off to the west. The walls were of rock; the roofs, non-existent or barely there. They had a melancholy look to them; it was as though they were being swallowed by the great expanse that surrounded them.

A few miles further along the road, I saw a band of horses; one group of seven animals, and a mare and foal off by themselves. I stopped the car and walked to the side of the road to set up my tripod and the larger cluster immediately moved farther away from me. I made a few exposures and decided I would try to get closer, but the horses ran to the edge of the wash while the closest one–a stallion and probably the alpha–stood his ground and began to snort and pound the ground with his hoof. From this behavior, I surmised that this was a wild band; the tame horses I have encountered are typically friendly and will even approach to within an arm’s length.

I took the hint and returned to the car. I didn’t want to alarm the animals any more than I already had. I didn’t make it more than a half mile further when I spotted a smaller group of three white horses on the south side of the road. These were more friendly, but still more stand-offish than usual. They continued their grazing, but were wary of my presence.

Now I dropped down into Kimbeto Wash, a key drainage for this part of the San Juan Basin. I came to a tee in the road; to the left, Ah Shi Sle Pah, to the right, unknown territory. I turned right and crossed Kimbeto Wash. Less than a quarter mile further along was a road to the left and a sign: Chaco Canyon miles. The mileage was illegible. Onward.

I was excited to find a back way into Chaco; connecting the dots on a map has always been satisfying for me. The road crossed a grassy plain with a low mesa on the southern horizon. The only other visible feature was a lone hogan about a hundred yards off the road to the west. After about ten miles there was a sharp left turn and the track dipped down and crossed Chaco Wash before continuing up to the top of a high plateau.

By now, I was firmly into a spontaneous wandering frame of mind; I took a turn onto a two-track that seemed to lead to the plateau’s edge, but the road curved back and dead-ended at an abandoned homestead, complete with old cars and trash burn barrels. I’ve seen hundreds of these forlorn dwellings scattered across the remote desert areas I frequent. They always put me in a pensive mood.

Back on the main road, I soon came to an intersection that put me on the main road into Chaco Canyon. I decided to make a quick tour of the loop.

One of the most interesting elements of the ancient pueblo culture for me is the kiva. There are different kinds of kivas: many were used as places for social gathering, but most of them were ceremonial in nature. These adjacent kivas at Chetro Ketl–the second largest pueblo complex in Chaco Canyon–were used for religious ceremonies. Standing near these centuries-old subterranean enclosures made me feel connected to the ones who contrived and built these amazing communities.

Chaco Canyon is actually comprised of many pueblo complexes which were built over a span of four centuries and housed thousands of permanent residents and visitors from outlying sites. Of these complexes, Pueblo Bonito is the largest with more than eight hundred rooms. Like most of the pueblos in Chaco Canyon, Pueblo Bonito is built close against the wall of the mesa.

A little further along the loop road from Pueblo Bonito is Pueblo del Arroyo. It is situated along the edge of Chaco Wash and had three hundred rooms; it is thought to have been built by residents of Pueblo Bonito who moved due to overcrowding in the larger site.

I had already spent more time at Chaco Canyon than I wanted to, so I made for the exit that brought me to Hwy 57 heading south. As I passed the boundary I stopped to make a photograph of Fajada Butte which rises 440 feet above the canyon floor and is home to the most famous of all the Chaco sites: The Sun Dagger site. Three slabs of rock are set up and arranged in such a way that shafts of sunlight shine through them and onto specific parts of a petroglyph carved on the rock wall of the butte on each of the solstices and eqinoxes. More proof that these early Americans were far more advanced than the “savages” they have been depicted to be.

So, with these thoughts bouncing around in my head, I left Chaco behind and continued my exploration of the San Juan Basin. New Mexico State Road 57 is not what you might expect from the designation. Soon after it starts at US 550 between Huerfano and Nageezi, it sheds its asphalt coat and becomes a dirt road in the truest sense of the word. A good rain will quickly turn it into a quagmire of greasy clay, the kind that will defeat even the most serious four-wheel drive vehicle.

So, although I truly enjoy a good thunderstorm, I couldn’t help but hope that the building thunderheads would hold their water at least until I made it to the pavement of Indian Rte. 9 twenty-five miles to the south. I was about half way between Chaco and the paved road when over a rise in the road came two beautiful horses. One of them, a mare, turned sideways in the road and seemed to be bowing to me. I was enchanted; I spent over half an hour with them and when I finally left them behind, it was with some reluctance.

The remainder of the drive on NM 57 was relatively uneventful. There were a few small clusters of hoodoos and several small herds of livestock and then, suddenly I was at the intersection with the paved road. I looked back the way I had come, again with some reluctance, and then turned onto Indian Rte. 9. Almost immediately I came across three horses drinking from a water barrel. The scene seemed to say a good deal about the nature of this remote area, so I made a photograph of it.

After its intersection with NM 57, Indian Rte. 9 climbs onto a low mesa and emerges at Pueblo Pintado, an outlier of the pueblos at Chaco Canyon. This area is still inhabited by the descendants of the anasazi people, but now they live in houses scattered across the mesa in the shadow of the ruin that was their ancestral home. Another thirty miles brought me to Torreon. It is here that IR 9 becomes New Mexico 197 and turns northeast towards Cuba, NM. I turned onto an un-numbered, but paved road that runs from Torreon to the small village of San Luis in the Rio Puerco Valley. I passed a rock ruin that I had photographed before, but I stopped to make several exposures before continuing on towards San Luis.

As I drew near San Luis and the Rio Puerco Valley, a heavy thunderstorm passed ahead of me, nearly obscuring the volcanic monolith of Cabezon Peak. It seemed a fitting end to my adventure. Even as I neared home my mind began wandering and wondering about another dirt road I had noticed meandering into the vastness of the San Juan Basin…

Roaming The San Juan Basin-Part1

The plan was to explore a small badlands on the Navajo Reservation. It is close to the settlement of Burnham, which is about half way between New Mexico Rte. 371 and US 491. I packed up the car early on July 4th and headed into the expanse of the San Juan Basin.

I have been wanting to make the drive across route 5 for some time, but I always put it off. The first half of the drive is unremarkable: a straight track across high desert grassland. As the road drops off the plateau, however things begin to get more interesting; the view opens up and you can see across the lowlands clear to the Chuska Mountains along the Arizona border. There are several volcanic plugs visible, including Shiprock on the distant northwest horizon.

These first two images show the landscape looking across the badlands from the top. One shows Shiprock in the distance, and the other is a view of the main part of the badlands area. The route to the bottom is gained by finding a trail across the bentonite hills and between the numerous small washes that drain the uplands. This is where a good GPS system was invaluable, The “breadcrumb” feature made it relatively easy to follow the path back to my car.

When I reached the bottom, I made my way to the most prominent feature, a tall gracefully eroded hoodoo atop a small mound. The colors are mostly yellows, blacks, and reds, the subtle gradients made an interesting compositional element, as did the small boulders strewn across the floor of the wash.

I had heard about a petrified stump somewhere in the area and I set out to locate it. I started by skirting the margins of the flats, moving in and out of each small drainage. I really had no point of reference, but since these badlands are relatively small, I felt confident that, if I kept looking, I would find the stump. I stopped to make a photo near the southern edge of the main wash and as I turned around to continue my search, I saw what I was looking for on the opposite side of a low outcropping. What I found most interesting about this particular piece was the nearly intact root extending down as if it was still doing its job of delivering water to the tree; such a commonplace relationship frozen in time and space.

I continued exploring for the next couple hours and found more petrified logs and small hoodoo groupings before making my way back to the car. As I began the climb back to the top, I made a photo across one of the tributary washes to the jumble of bentonite mounds that surround the lowlands.

As I continued the climb out, I made several more images, including the one below, looking westward to the Chuska Mountains. I was thankful for my GPS, I had to reference the “breadcrumb” feature a couple times to find my way out of the maze.

When I reached the car, I realized that it was still relatively early in the day. Looking out over the landscape, I once again saw Shiprock on the horizon and decided to drive there to photograph it at sunset, hoping for some nice color in the overcast sky. I returned to IR-5 and continued west to its junction with US 491 and then headed north to my destination.

I drove onto the dirt road just east of the lava dike and followed it for a couple miles until I found a good spot and began the wait; there was still a couple hours to go before sunset. I set up my camera and tripod, made a few exposures, and repositioned the setup. I then settled in to wait for the anticipated light show. I made exposures whenever the light was interesting, and read a book I had brought along to help pass the time. In the end, sunset was not what I had hoped it would be, the clouds grew more dense obliterating the evening light and muting what little color there was. But, I had plenty of images with some nice light to choose from. This is my pick out of those, the side-lighting does a nice job of revealing the rugged texture of Shiprock, and also casts a nice glow across the foreground.

I drove to Farmington to spend the night satisfied that I had come away with some good images. I decided that I would extend the trip through the next day and see where the wind would take me.

The Rio Puerco In Bloom

The Rio Puerco Valley is an arid place. The colors are usually limited to browns and sparse, muted greens. But, in a good year, when there are generous spring rains and a healthy monsoon, the desert comes alive; late spring, and early summer will see an abundance of colorful blossoms on the cacti, and the shrubs that grow and cover the landscape as far as the eye can see.

Since we are currently experiencing those very conditions here in the high desert of northern New Mexico, I was excited to see a cane cholla covered with reddish-purple blossoms as I was driving home a few days ago. The next day I packed my gear and headed into the expanse of the Rio Puerco Valley, certain that I would find it full of blooming chollas.

My expectations were confirmed as soon as I turned onto the county road that leads into the valley. The rolling plains on both sides of the road were covered with cane chollas and flowering plants in bloom. As I made my way through the small village of San Luis and deeper into the broad valley, my excitement grew. Everywhere I looked, it seemed, were colorful blossoms–mostly reddish/purple or yellow.

The day was pregnant with possibilities; the weather was stormy, and as I watched from deep in the wilderness, a cloud opened and began dropping virga over the landscape. Virga is an observable precipitation that drops from a cloud, but evaporates before it reaches the ground. I managed to make several good images that contained the event before it dissipated.

A lone cholla blooms as a summer rainstorm passes over Cerro Guadalupe, Cabezon Peak, and Cerro Santa Clara

By the time I reached the ghost town of Guadalupe, I had already made over two hundred images and there was still plenty more to do. I parked the car and walked through the familiar landscape. I had photographed in Guadalupe many times before, but never with the desert in bloom the way it was now. This was a remarkable contraposition between the hope of prolific reproduction and the disappointment of broken dreams.

A cholla blooms in the ghost town of Guadalupe, New Mexico in a remote section of the Rio Puerco Valley

When you have photographed an area as much as I have photographed Guadalupe, it can be difficult to remain fresh, to create something new, but the chollas, which I usually see as just another part of the landscape, were now transformed into something more. I was able to see and use them as elements of counterpoint in my compositions. I think that made a big difference in how I saw the scene, and created the images.

A lone Cane Cholla bears witness to the slow decay of adobe buildings in the ghost town of Guadalupe, New Mexico in a remote section of the Rio Puerco Valley

One image in particular required that I step out of the box. There is a section of wall that remains standing while totally separated from the rest of the building it had been part of. Several years ago, I made an image of the wall with a crumbling two-storey building visible through the door opening. Being a creature of habit, it tried (unsuccessfully) to frame both the building and a blooming cholla in the opening. I finally gave up, and as I was walking away, I turned and saw what became the above image. I love it when failure leads to success.