Shipwreck-Low Tide

The Peter Iredale ran aground in heavy fog while trying to enter the Columbia River channel in October of 1906. The wreckage is still there today just west of the small town of Warrenton. The day I showed up to photograph the wreck, the conditions were just right. The thick overcast created a somber setting; all I had to do was wait for low tide so I could position the breaking waves where I wanted them in the image and capture the reflection and wave patterns in the wet sand.

I used my Nikon D810 with a Nikkor 24-120 f4 lens mounted on a Bogen-Manfrotto tripod. Post processing was done in Adobe Lightroom and Adobe Photoshop. Black and white conversion was done in Silver Efex Pro.

2015’s Best Part 1

2015 was an exceptional year for me in terms of photography. Not just for the images, but for the experiences as well. I made an effort to be more adventurous, and spontaneous in my choice of subject matter. I also vowed to be more responsive to the images themselves when it came to post processing. In all, there are thirty-seven photographs, so I will present this post in two parts. I hope you enjoy viewing them as much as I enjoyed making them.

In late January we had a heavy snowfall which made it impossible for me to drive out of my driveway. So, I walked down to Soda Dam to photograph it in its winter splendor. This image seemed to be a black and white candidate from the start.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70 f2.8: 1.3 sec., f20, ISO 50

March took me to southern Arizona to photograph desert wildflowers. I didn’t find the showing I had hoped for, so I contented myself by pursuing Teddy Bear Chollas. When photographed in the right light, they have a luminous quality about them. I made this image at sunset in the Lost Dutchman State Park, east of Pheonix. The fabled Superstition Mountains lie on the horizon.

Nikon D800 with 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1.3 sec, f16, ISO 50

I’ve been to Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash many times over the years, but I seldom explore along the southern edge. In April I decided to change that; I made this image looking northwest from the top of the southern rim. This is the section I call the Yellow Badlands. It’s like taking a look back through time.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70 f2.8: 1⁄8 sec, f18, ISO 50

In May while exploring a part of Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash I had never been to before, I came across this incredible hoodoo hidden in a small ravine along the northern edge of the main wash. I stayed and worked the area for nearly two hours. This is the first of many compositions using what I call the Neural Hoodoo as the main subject.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 16-35mm f4 lens: 1⁄30 sec, f16, ISO 50

This black and white image was made from the opposite side of the Neural Hoodoo. If forced to choose a favorite, this would be it.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 16-35mm f4 lens: 1⁄25 sec, f16, ISO 50

This final image of the Neural Hoodoo was made from the same general location as the first, but I zoomed in to capture a more intimate portrait.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 16-35mm f4 lens: 1⁄15 sec, f16, ISO 50

At the same time I was exploring the far reaches of Ah Shi SlePah, I was discovering some of the amazing and convoluted drainages along the southern rim of the wash. I made this image on a stormy evening in late May. I could not have asked for more appropriate light for this scene.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄60 sec, f18, ISO 50

In early June I went out to the Bisti Wilderness. At the far reaches of the southern drainage, I made this image of a multi-colored grouping of hoodoos. I had photographed this same group several times in the past, but I think this is my favorite. The clouds seem to reflect the lines of the caprocks.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70 mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄40 sec, f16, ISO 50

One morning in late June I noticed the chollas around my house were blooming. I set out the next morning for the Rio Puerto Valley to capture the splashes of color in that dramatic landscape. I made the first image (above) in the ghost town of Guadalupe. The return of life to the desert seemed coincidental to the ongoing decay of the adobe buildings.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄6 sec, f16, ISO 50

In this image, a blossoming cholla stands at the head of a deep wash as a rain cloud passes over Cerro Cuate in the distance. Even the slightest precipitation sustains life in this environment.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄10 sec, f16, ISO 50

Early on the morning of July 4th, before the road was closed for the parade, I slipped out of town and drove out into the San Juan Basin. I didn’t really have a plan other than to visit the Burnham Badlands, which lies to the west of the Bisti Wilderness, and covers a relatively small area as badlands go (about one mile by two miles). This graceful hoodoo sits smack in the center of it.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄20 sec, f16, ISO 50

After completing my exploration of the Burnham Badlands, I drove west through the heart of the Navajo Reservation and arrived at Shiprock in the early evening. I drove one of the dirt roads that runs along the lava dike until I found a spot I liked. I set up my camera and tripod then waited for the light. Over the next two and a half hours, I made almost a hundred exposures as the light changed and the sun crept toward the horizon. This is my pick.

Nikon D800 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄6 sec, f16, ISO 50

Hidden in plain sight, just a few miles north of Ah Shi Sle Pah is the Fossil Forest. At the end of a low ridge which runs east to west, you can just make out the telltale signs from the county road: the striated color, and the deep cut drainages where geologic treasures lie exposed. I went there with an agenda: to find a fossilized tree stump. I’ve related the whole story in an earlier post, so I’ll just say here that we were able to locate the stump after some scrambling and sleuthing.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 16-35mm f4 lens: 1⁄25 sec, f16, ISO 100

In July, I made a trip to visit my daughter Lauren in Madison, Wisconsin. She accompanied me on the return trip. Early on the second morning, somewhere in central Kansas, she mentioned the large birds roosting on the fence. I had driven past and hadn’t noticed them, so I backtracked until we found them. The birds turned out to be a committee of turkey vultures sunning themselves and drying their wings. I was able to get pretty close to them without distressing them, and I managed to capture quite a few exposures. This is my favorite.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 24-120mm f4 lens: 1⁄640 sec, f9, ISO 500

In August we set out on the high road to Taos. The way passes through many small villages: Chimayo, Truchas, Las Trampas, and Picuris Pueblo to name but a few. At Picuris, we visited the plaza, and there, I noticed the shapes and texture of the adobe walls of a small church. This is the result of my efforts there.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 24-120mm f4 lens: 1⁄400 sec, f14, ISO 1600

Farther up the road, we took a fork to visit the village of Tres Ritos. There, in a meadow by the side of the road, was a spray of mountain asters with a small wetland full of cattails just beyond it. The dark foreboding sky intensified the saturation of the colors and was the perfect backdrop for the scene.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄640 sec, f16, ISO 1600

In late August on a trip to Denver, I drove up highway 285 instead of using the interstate. Late in the day, the clouds were hanging in tatters from the peaks of the Sangre de Cristos to the east. The grasses were just beginning to turn and the colors filled the spectrum. When I came across the trees, it all came together.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 24-70mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄5 sec, f11, ISO 50

On my return from Denver, I was driving across the Taos Plateau and the nearly full moon was climbing through the clouds above the Sangres. The Chamisa was in bloom and all I needed to do was find the right combination.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 80-200mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄500 sec, f13, ISO 800

Still on the Taos Plateau. The texture and colors in the grasses and sage, along with the rays of sunlight piercing the dark clouds caused me to pull over again (at this rate, I would never get home). The lonesome Ponderosa Pine anchors this image, but the thing that really ties it all together is the thin strip of light colored ground below the mountains.

Nikon D700 with Nikkor 80-200mm f2.8 lens: 1⁄500 sec, f11, ISO 800

The Badlands Of The San Juan Basin

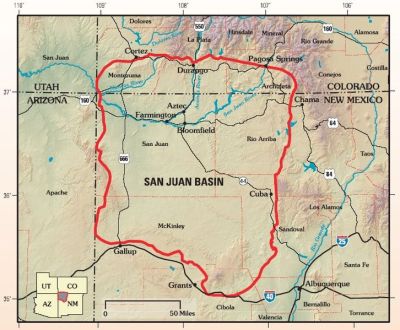

The San Juan Basin is a large, roughly circular, depression that lies in the northwest corner of New Mexico, and is a part of the larger Colorado Plateau. What makes the basin special is the fact that, at one time, it was in an area that was covered by the Western Interior Seaway, a prehistoric body of saltwater that split the North American continent from top to bottom.

The location along the shores of a large body of water in a tropical climate allowed an incredibly diverse ecosystem to thrive. As these life forms died, they decomposed and were eventually covered by volcanic ash from the eruption of nearby volcanoes. As the seawater covered the area more sedimentation sifted over the remains and some of the sediment was infused with mineral rich water that seeped through the layers above making it harder than the surrounding matrix. This was an important step in the formation of the present-day hoodoos. The weight of the water compacted the entire assemblage, and it was lost to the the world above the waves.

About 65 million years ago, the waters receded and a layer of sediment nearly two miles thick was left behind. Since then, plate tectonics, volcanism, and glacial erosion have helped to shape the present-day San Juan Basin. Further erosion from wind, water, and annual freeze/thaw cycles exposed the hardened sediment layers which eroded more slowly than the softer sand/ash matrix. The result is a wonderland of hoodoo gardens that are especially obvious along the edges of the many washes that criss-cross the basin. Some of these drainages such as Ah Shi Sle Pah, Hunter and Alamo–the two washes that formed the Bisti, and their tributaries have carved and exposed a treasure trove of unlikely works of earthen art.

The human history of the badlands is of course relatively short. Probably the most significant event in shaping the area in the last hundred years was the discovery of coal and the associated coal-bed methane. By the early 1980’s coal mining, mostly to fuel the nearby Four Corners Power Plant, was consuming large tracts of land throughout the basin. Inevitably, the Bisti became the center of a lawsuit between the Public Service Company of New Mexico and the Sierra Club; PNM already had a mining operation there and it looked like it might become just another large open-pit mine. However, the courts sided with the Sierra Club and in 1984, the Bisti was awarded wilderness status. In recent years, Ah Shi Sle Pah has also become a Wilderness Study Area. So, at least for the present, these gems are safe from the insatiable maw of “progress”.

Of the nine recognized badlands in the San Juan Basin, the Bisti is the largest–at 30,000 acres–and most well known. It includes the Kirtland and Fruitland geologic layers and was deposited 70-75 million years ago. The chief deposits are: sandstone, siltstone, shale, coal, and volcanic ash. Fossils include remains of T-Rex and large cypress-like conifers.

Ah Shi Sle Pah is much smaller than the Bisti, but was deposited around the same time, and thus contains the same geologic layers. It contains the same deposits: sandstone, siltstone, shale, coal, and volcanic ash. The fossils found in Ah Shi Sle Pah include remains of crocodiles, Pentaceratops (which has been found only in Ah Shi Sle Pah), early mammals, and of course, petrified wood.

The other recognized badlands in the basin are: Ojito–the oldest having been deposited 144-150 million years ago–, De Na Zin (70 -75 million years ago), Lybrook, Ceja Pelon, Penistaja (all 60-64 million years ago), San Jose (38-64 million years ago), and the youngest, Mesa de Cuba (38-54 million years ago).

The map shows the boundaries of the San Juan Basin. Rather than being formed by volcanism like the San Juan and Jemez Mountains to the north and east, the basin was uplifted as a single block after which the center collapsed to create the basin.

The idea for this post came from a show I had last year called Badlands Black and White. I chose to print all the images in B&W in order to focus on the graphic elements: tone, texture, patterns, etc.

This image was made in Alamo Wash in the Bisti Wilderness. The cracks that result from the shrinkage of the clay rich soil tell a story of the arid environment. The sandstone balanced on the short mudstone pillars is an example of the hardened sediment and how it weathers in relation to the softer layers below it.

The floor of most badlands is usually littered with small pieces of debris, which is comprised of bits that have broken or eroded from larger structures. They can be shale, clinkers (super-heated clay), siltstone, or even glacial deposits from the last ice age. There are often fossilized bone and clamshells mixed in with all or some of the above.

I made this image of a client while leading a tour in the Bisti Wilderness. The man is standing on an ridge above a deep wash in the Brown Hoodoos section of the wilderness. I wanted to give the viewer a sense of scale and the feeling of being lost in the bizarre surroundings.

These eroded pillars are in a small alcove located in a tributary of Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash. Some of them still have their sandstone caprocks, while some have lost theirs. The badlands are an evolving story of creation and degeneration, once the protective cover of the caprock is gone, the erosion process proceeds at a much faster pace.

This image is from Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash. The squat hoodoos in the foreground are relatively new and haven’t weathered out to the extent that some of the taller, more widely spaced ones have. Like many of the places I frequent in the badlands, I can’t visit this one without making several exposures.

At Ah Shi Sle Pah, there is a small, raised enclosure; I call it the Dragon’s Nest. What caught my eye the first time I saw it were the patterns and textures eroded into the solidified volcanic ash. This formation, at some time in the past, probably had a sandstone cap-rock.

I made this image in Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash. This collection of hoodoos sits in the middle of a labyrinthine tributary wash. The small column on the right has lost its caprock and is undergoing accelerated erosion.

This is a formation in the Bisti Wilderness that I call the Queen Bee. It is part of a small area of similar formations known as the Egg Garden. The cylindrical shape of these eroded forms is due to them being formed and hardened inside limestone tubes. As the surrounding layers eroded away, they emerged as distinct egg-shaped forms. The Egg Garden is one of the most popular attractions in the Bisti.

This small arch is another feature that brings people come from around the world to visit the Bisti Wilderness. The Bisti Arch can be deceiving; the opening is only about three feet across and half as high. The first time I found it, after searching unsuccessfully during previous visits, I was surprised by how small it is. The top of the arch is made of siltstone supported by a volcanic ash pedestal, and was once part of a wall which stretched across Alamo Wash.

In his book “Bisti” which was printed in the 1980’s, David Scheinbaum included an image of this formation with the caption: “This unstable hoodoo is just within the Sunbelt coal-mining lease and will probably be destroyed by mining in the near future.” I made this image on a recent trip to the Bisti Wilderness, and I’m happy to report that the unstable hoodoo is still standing.

A Separate Reality

It has been well documented that color steals the show when it comes to viewing a photograph. I have written about this previously, but as I have evolved as an artist, my ideas concerning visualization have also progressed. When you look at the two versions of the image below, what is the thing that grabs your attention? What is it that makes one version better or more visually pleasing to you? Do you have the same emotional response to both, or do they each evoke a different reaction?

I love the shade of green in the color photograph. All the variations of shading change subtly from one tone to the next, the trees in the background are almost an afterthought. It is a relatively peaceful image.

The second version is rendered in black and white. There is more tension between the elements because the background trees are no longer visually less dominant. Their repetitive verticality vies for attention with the more random shapes and lines in the False Hellebore in the foreground. The contrast in tonality is also more obvious in the second version, making the image more visually aggressive.

I don’t mean to say that the black and white image is more successful in portraying the feeling I had when I recorded the scene, I am just pointing out that each version places more emphasis on certain elements in the composition. The result is two separate realities (apologies to Carlos Castaneda) that convey two different emotional responses to the same subject.

Sanding The Stone

Telling a story about a place using images isn’t necessarily as straightforward as it may seem. There are many layers of information; some need to be added to, others subtracted from. In the case of the badlands of the San Juan Basin, the latter is the case.

The landscape itself is in fact formed by subtraction. It is eroded by the force of wind, and water over time. Things are not always as they appear. The tree trunk in the first image is no longer composed of wood; it has, over time, become transformed by minerals that replaced the dead organic matter, making it a petrified semblance of its former self.

This layered channel sandstone was infused with minerals which leeched into the ground making it harder than the surrounding matrix. As the accumulated sedimentation eroded, the harder stone was left exposed.

Much like the landscape, these photographs were created by removing some of the information, more specifically, the color. A black and white image presents the bare bones of the subject and allows the viewer to see the underlying structure.

Most of us are subconsciously influenced by colors. We make associations between colors and a certain emotion or mood, so removing the color eliminates the preconceived idea, which in turn leaves us free to experience an image in a more visceral way.

The badlands are a visual experience; the textures, shapes, and patterns inherent in the stone and clay are extraordinarily diverse. So, whether the image is one of more intimate proportions as in this photograph of a small alcove in Ah Shi Sle Pah, or of a grander scale like the image of the Bisti Arch shown below, the simplicity of the black and white image allows the landscape to stand on its own merits.

And while the yellows, reds, browns, greens and magentas which paint these amazing places with an astounding palette, play a role in telling the whole story, the absence of those colors conveys the essence of their austere beauty.

That Was Then; This Is Now

Yesterday I cleaned my cameras and lenses…all of them. It took me all of the morning and part of the afternoon. I hadn’t handled my Nikkormat FTN in quite a while, but it felt like an old friend which, in fact, it is. It is the first SLR I ever owned; I bought it in 1971 at the PX while I was overseas. At that time, the FTN was a favorite of photojournalists covering the Vietnam War because of it’s sturdy construction. It is now considered a classic. While I had it out I decided to pose it next to my latest DSLR–a Nikon D800.

The juxtaposition started me thinking about how photography has changed over the forty plus years since I bought that Nikkormat. There have been many upgrades to the Nikon line in that time; I own several of them: two Nikkormat FTNs, an F3, and two F 100s. But, the changes over the past ten years have actually been a paradigm shift. Of course I’m referring to the advent and rapid growth and development of digital photography.

I wanted to do a comparison of the work I was doing then and the work I’m doing now, so I dusted off my collection of old negatives and prints to see what I could find. In those days, I shot primarily Kodak Plus X (ASA/ISO 125) and Kodak Tri X (ASA/ISO 400). I developed and printed all of these early images in a “wet” darkroom, and although I get a bit nostalgic looking at them, I don’t regret my switch to the digital realm. True to form, once I crossed over I never looked back.

This is a self-portrait I made just before I was discharged from the army. I was really into dramatic side-lighting at that time. I made dozens of portraits of friends from my unit and they are all lit the same way. When I shoot portraits now, I usually use at least one flashgun, on camera or off, umbrellas, reflectors…Seeing these simple available light images makes me realize how effective that kind of lighting can be. I do miss the catchlights though.

Nikkormat FTN, Nikkor 50mm f1.4

My friend Kim Bong In and I went to Inchon to do some sight-seeing. I made this portrait of him at the Inchon Memorial Pagoda. Kim was a DJ at one of the clubs in Tongducheon which is the village next to Camp Casey where I was stationed. He and I became friends during the time I was there, and he introduced me to everyday Korean life, the one beyond the clubs and “working girls” which is all most GIs ever saw. I went to his grandfather’s funeral and was invited to the celebration when his son was born.

Nikkormat FTN, Nikkor 135mm f2.8

I caught these four young chin-gus (friends) hanging out on a busy thoroughfare in Inchon. Their expressions were all over the map: unguarded disdain, shy curiosity, nervous apprehension, watchful suspicion. Ours was a brief encounter; they went their way and I went mine. But, looking at this image more than forty years later, I wonder how their lives have played out. I wonder if the expressions they wore that day reflected the men they would become.

Nikkormat FTN, Nikkor 50mm f1.4

Once you made your way beyond the section of the village that tailored to the American servicemen, you found yourself in a different place and time. There were no supermarkets, the people bought their food at small street markets like this one. The woman in the center of the image was obviously in charge. Her produce is arranged rather haphazardly around her, cuts of meat hung in a display window. I was telling a story here. I was in a photojournalistic frame of mind.

Nikkormat FTN, Nikkor 35mm f2.8

I got to know this Korean elder through regular interaction with him in the village. We communicated with pidgin Korean and English. I don’t remember his name, but he was kind enough to pose for this portrait. The one thing I don’t care for in this image is the slight motion blur. Because I was pretty new to shooting with an SLR, my camera technique was not very good. I remember that I usually shot somewhere between 1/125th and 1/200th second, but there were times when I would end up down around 1/60th and this was probably one of those times.

Nikkormat FTN, Nikkor 105mm f2.8

Fast forward to 2014. I have lived in the small village of Jemez Springs, New Mexico for thirty-nine years. Not much has changed as far as the eye can see. It’s a sleepy place, especially on a Wednesday night in January. I handheld my camera while making this image. I dialed the ISO up to where I needed it to get a suitable shutter speed with an aperture of f8. I reduced what noise there was in Lightroom. This would not have been possible with the available technology just a few years ago, let alone in the 1970s.

Nikon D700, Nikkor 28-70mm f2.8

I’m not big on self-portraits. But, there are times when the location demands one. I spent several years trying to find this stone wing which is located deep in the heart of the San Juan Basin. When I finally located it with some help from a photographer from southern California using Google Earth, the actual experience was a bit anti-climactic. I decided to pose Robin and myself under the cantilever with the waxing gibbous moon overhead.

Nikon D700, Nikkor 17-35mm f2.8

One thing I’ve learned over the years is that if you want to make good portraits, you need to be able to engage your models. It’s not the easiest thing to approach a stranger and, in a short time, make him comfortable enough to open up to you. So, when I saw this fellow at a powwow last year, I went over and started talking to him. Predictably, he was a bit stand-offish at first, but after a while, the walls came down and he agreed to pose for me.

Nikon D800, Nikkor 28-70mm f2.8

My youngest daughter Susan is a natural when it comes to modeling. I made this image of her at a waterfall not far from my home. It was shot RAW as are all of my images; I converted it to black and white and added a sepia split tone in post processing. This kind of control over the ultimate look of an image is only possible by taking advantage of a RAW workflow.

Nikon D300, Nikkor 28-70mm f2.8

At the end of last summer, I travelled to Wisconsin where my daughter and her husband live. We spent part of that time in Bayfield on the coast of Lake Superior. While relaxing on the porch of the house where we stayed, I made this image of them.

In looking back over my development as photographer, I see that I have come full circle. I am technically more proficient than I was when I started, and the visual journey I have made has enabled me to add another layer to my vision. It’s evolution and that’s what it’s all about.

Nikon D700, Nikkor 24-120mm f4

My Few Of My Favorite Things

Wow! Another year fades into memory. I have spent the last couple weeks editing the images I’ve made in 2013 with the goal of culling my favorite dozen. Image editing for me is a labor of love; I have a connection to my work, so picking “the best” out of hundreds candidates is not an easy task.

I knew from the time I made this photo of a bull elk in my yard on January 3rd that I was setting a high standard for the rest of the year. Also, not only was it serendipitous, but the image was a departure from my usual wide angle landscapes. I had been feeling for some time that my work had been stagnating, so I resolved then and there to take it in a new direction.

In early February, I ventured into an area along US 550 that I had been looking at as a shooting location for some time. I was drawn by some red sandstone pinnacles that were visible from the highway. As I walked toward them, I came across this old section of road that is slowly eroding, being reclaimed by natural forces. The scene made me realize how impermanent our impact on nature really is. In the end, this is the image that stood out above the others I made that day. Again: serendipity.

As the year progressed, I found myself revisiting some places I had been before. The image of the church on San Ildefonso Pueblo (a scene I had driven past countless times before) is more about the light than the subject matter. It is also a more visually compressed image than is usual for me due to my use of a longer focal length lens.

Every year at the end of May–Memorial Day Weekend to be exact–the Pueblo of Jemez hosts the Starfeather Pow Wow. Hundreds of native dancers from across the country come to dance and compete. I made hundreds of images that weekend, but this portrait of two brothers stood out. They are dressed in “dog soldier” head-dresses, hair-pipe breastplates, and feather bustles, all made by their father. Just before I released the shutter, I told them to give me some attitude. I think they did a pretty good job.

Anyone who is familiar with my work, knows that I spend a great deal of time in the Rio Puerco Valley. It was near the middle of July and the rains had just started after several months of searing heat and cloudless skies when I made this image. There are many possible causes for this animal’s demise, but the location of its desiccated remains along a now rain-filled wash and the rain falling from a heavy sky tells an ironic story about the uncertainty of life in this harsh environment.

And speaking of harsh environments, the Bisti Wilderness in July can be a sobering place. The temperatures can soar to well over 100°F. I usually try to discourage clients from booking a photo tour during this time, but if the monsoons have started, it can be relatively pleasant and the cloudy skies lend a sense of drama to the scene. I made this image of one of my clients pondering the maze in the Brown Hoodoos section of the wilderness.

From a land of parched earth to a place where water is omni-present; my travels took me to Wisconsin in August. On a day-trip to Olbricht Botanical Gardens with my daughter, I made this image of the Thai Pagoda. Normally I steer clear of this kind of symmetry in a photograph, but the structure, and the entire environment seemed to demand it.

Autumn is the best time to be in the badlands, especially if the atmosphere cooperates. Even though the ground was soft and the washes were running from the rain, there were still cracks in the earth. It was as though the soil had a memory of the scorching it normally receives and refused to let go. After processing this image, I realized that it was best to convert it to black and white.

During the months of September and October I spent a great deal of time photographing the trains of the Cumbres-Toltec narrow-gauge railroad which runs from Chama, New Mexico to Antonito, Colorado. I spent every weekend for nearly a month chasing the trains and the fall colors. In the end, my favorite image had nothing to do with color and everything to do with the train, the track and the trestle.

To most people, in the US anyway, November means thanksgiving. For me it is my annual trip to Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge. Over the years, I have come to relish my time with the cranes, herons, geese, and other waterfowl that call the Bosque home during the winter months. Even though I have thousands of images of the birds flying, taking wing, landing, wading, eating, and doing whatever else it is that they do, I still managed to make two of my favorites there in 2013.

This first is obvious and familiar: a crane in the process of taking off from one of the ponds to fly to the fields where he will spend the day foraging. The second is a departure from my normal Bosque images, but one that illustrates the reason that I keep returning year after year.

In December I travelled by train to visit my oldest daughter (an adventure I wrote about in my previous blog entry). Chicago’s Union Station was a surprise to me. I made several images inside the station and when I wandered out the doors to Canal Street, I found this scene. I was immediately drawn by the fact that while some of the elements had symmetry–there’s that word again–some didn’t. And of course the cherry-on-top: the wet pavement reflecting the lights and columns.

To B&W Or Not To B&W

What is it about a black and white image that fires our imagination? How does the removal of color from an image have such profound effect on what that image says to the person viewing it? In this post I am going to look at three of my photographs and discuss how the black and white versions differ from their color counter-parts.

This first image was made at Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash in New Mexico’s San Juan Basin. The gibbous moon was riding low in the sky and I captured its transit behind this rock formation. In the color version, while the moon is still center stage, it is overpowered by the strong contrast between the complimentary colors in the sky and the orangish brown rock.

In the black and white image, the moon regains its prominence; even though it is relatively small in the photo, the contrast between it and the dark sky gives it some visual weight in the frame. The foreground is suddenly more about the mudstone supporting the rock, again because of the lighter tones in that part of the image.

Another element that benefits from a black and white conversion is a textured pattern. This image of the cracked earth near the Eagle’s Nest in the Bisti Wilderness does pretty well in color, but when converted to black and white, the texture in the foreground becomes more prominent.

The image is suddenly more about the dry cracked earth which was my intent.

Sometimes it’s more about the overall feel of the image. This last photo of the Cumbres-Toltec was made as the train was crossing the bridge over the Chama River. I like the color version but the mood isn’t quite right. By converting the image to black and white and then adding a sepia split tone, I was able to pull the image together and give it a more somber voice.

There are many ways to accomplish a monotone conversion using Photoshop, Lightroom, or any of the other image editing applications that are available. The most important part of the process, I believe, is having the ability to control the tones as they relate to the colors in the original image. By using the B&W adjustment layer in Photoshop instead of a greyscale conversion (which dumps all of the color information), or the HSL sliders in Lightroom you can adjust these tones individually and your results will have more visual punch.

Wheels In The Landscape

There was a time not so long ago when I would have gone to extraordinary lengths to exclude anything man-made from my images. But I slowly came to realize that I was being narrow-minded and losing some great photo opportunities. After removing the blinders from my artistic vision I suddenly became aware of new possibilities with subjects I would have previously rejected without a second thought.

I first came upon this car about five miles from where it now sits in the Rio Puerco Valley. I had made a second trip to its original location only to find it had been removed. I thought it odd that someone had gone to the trouble of dragging it out of the small side canyon accessible only by a two track dirt road, but then I thought that perhaps the BLM was making an attempt to tidy up the valley. It is, after all, a wilderness study area. Imagine my surprise to find the old, rusted, topless vehicle parked (for lack of a better word) in the “yard” of a tumble down adobe/rock house not far from Cabezon Peak.

I made this second image while driving through the panhandle of Texas. This whimsical installation lies along Interstate 40 east of Amarillo; I had my youngest daughter in mind when I was making the exposures. She loves VWs.

The image of the bus and the car were made along Torreon Wash near the Empedrado Wilderness Study Area near Cabezon Peak in the Rio Puerco Valley. The bus sits on rusted wheels and is full of old insulation and rat droppings suggesting that it is (was) being used as a storage shed for some nearby construction.

The car sits near an adobe/rock ruin. It is sunk to the rims in the clay soil and so its fate appears to be sealed.

This 1950s era Ford is parked in front of one of the rooms at the Wigwam Motel in Holbrook, Arizona. There are several other old vehicles parked in front of other rooms. I can’t be positive, but I highly suspect that the creators of the Disney animated movie “Cars” may have used the Wigwam as a model for the motel in the movie.

The last image was the result of accidentally being in the right place at the right time. I was driving from Albuquerque to Los Alamos by way of Santa Fe. I pulled off I-25 at the exit where the AT&SF rails cross beneath the interstate. My plan was to get down on the tracks to make an image for my Road Series (as in rail ROAD). As I was walking across the bridge above the tracks on the frontage road, I heard the whistle and soon after that I saw the Amtrak Southwest Chief come through the cut and approaching the bend in the distance.

Mud, Stones, and Wood

There is no shortage of adobe ruins in the American southwest and there is also no shortage of photographs of those ruins. This poses a dilemma for photographers who want to find fresh ways of capturing an image.

So, how many ways are there to photograph ruins? I decided to share some of my techniques for making eye catching images of an often photographed theme. In the first image, I asked myself: “What drew your attention to this scene in the first place?” The answer: the corrugated tin roof and the color and grain of the door. So, I made a selection of those elements, inverted the selection, converted it to B&W, and added a sepia tint.

I made the second image in the ghost town of Guadalupe, New Mexico in the Rio Puerco Valley. I had photographed the two storey ruin many times, but this time I was looking for something different. I was walking around the small village, in and out of various ruined buildings when I saw this image just waiting for me. By framing the larger building in the doorway, I managed to say more about the entire village while still making a fresh image of the subject.

Here is a more intimate scene. By de-saturating the adobe walls and warming the remaining color, I was able to create the effect of a glow from the inside of this old ruin.

This last image was taken from an overlook several hundred feet above and about an eighth of a mile from the Mummy Cave Ruin in Canyon del Muerto, a side canyon of Canyon de Chelly. I used my 80-200 f2.8 Nikkor lens at 200mm. I thought about putting on my 400mm lens to get a tighter shot, but then realized that this magnification was perfect: it allowed me to show the subject in context; including the towering rock face above the ruin says much more about it than if I would have zoomed in for a tighter crop.

A Metamorphic Paradigm

There are places and scenes that I have photographed so extensively that I often think I shouldn’t bother to make yet another exposure. After all, if you’ve photographed something once, there’s no need to waste time doing it again. Right?

Some of these places have a kind of power over me. It seems I can’t go near without setting up my gear and making an image. That’s as it should be; it’s wrong to think that there is only one image waiting for you in any given location or subject. There is no end to the ways something can be photographed if you dig deep into your bag of creative tricks. The Bisti Arch in the Bisti Wilderness is one of the places that always draws me to it.

Some of these places have a kind of power over me. It seems I can’t go near without setting up my gear and making an image. That’s as it should be; it’s wrong to think that there is only one image waiting for you in any given location or subject. There is no end to the ways something can be photographed if you dig deep into your bag of creative tricks. The Bisti Arch in the Bisti Wilderness is one of the places that always draws me to it.

I have been to the arch many times. Every time I lead a Photo Tour to the Bisti, I take my clients there, and every time I go on one of my own outings, I find myself there. I could try to take a “been there, done that” attitude, but then that little voice starts haranguing me and I’m soon happily engaged in the process of composing and making photographs.

The result is a rather large collection of images of this formation (and others that I am drawn to in the same way). But, I try to give each version its own voice; whether I change the point of view or the focal length of the lens, or process the image differently, each of the resulting photographs portrays the subject in a unique way.

Sometimes, as in the above image, I give the feature a bit part, making it part of the background with other elements leading the eye to it. And sometimes I change the point of view dramatically

so the viewer may not even realize that it is the same place. The point I’m trying to make here is that making images of places or subjects that you have photographed numerous times need not be a repetitive chore. If you study the place and its environment, there are many ways you can come up with a fresh perspective and a new way of presenting your subject.

The Evolution Of Vision

Artistic vision is not something that is easy to define, at least not in terms of individual style. It is something that is (or should) always be changing, evolving. When I look at the work that I was doing five years ago, I am struck by the difference from that which I am doing today. That’s as it should be. If I could see no discernible change, I would be worried that my creativity is stagnating.

Vision has to do not only with the subject matter you shoot, or the way you choose to capture it. It is also about how you take the image from the one in the camera to the one that hangs on the wall. So, post processing is just as important to expressing your vision as the initial capture, perhaps more important. This first image was made one January day on the edge of what was soon to become the Valles Caldera National Preserve and after many years of learning and evolving, both in my shooting style and in my processing technique, this is still one of my favorite photographs.

I tell my Beginning Digital Photography students that they should always be looking for new ways to present their subjects and of course this extends to the work they do in the digital darkroom. I made the above image in 2002. It is a close-up of burned tree bark that I took in the burn scar of the Lake Fire. This is pretty representative of the work I was doing at that time: close-up/macro/intimate landscapes.

The third image was made several years later and it is one of the very few I made during that time that included a hint of anything man-made. All of these photographs were made using film cameras. The first two were shot with a Nikon F3, the second, a Nikon F100. All three were made using Fuji Velvia transparency film.

Sometime around 2005, I began to feel that my strict adherence to shooting almost exclusively macro/close-ups was stifling my creativity and I began to broaden my horizons (both literally and figuratively). I had also purchased my first digital camera, a Nikon D200. Looking back, I think the new-found freedom of no longer being constrained by the cost of film played a major role in my ability to experiment with a new shooting style.

This black and white landscape was an early attempt to further break from my habit of excluding man-made elements from my images. I still hadn’t perfected my B&W conversion technique, but it was a step in the right direction.

When I was shooting mostly macro, I preferred diffuse lighting; no shadows means clearer details, but as I began to see the broad landscape, I began to take advantage of the multi-faceted nature of light. In the five images above, I make use of different kinds of lighting: overcast, early morning, evening, and mid-day with partial overcast. They each paint the landscape with a different brush and each portrays a different mood.

Lately, my work has come full circle, back to the subjects I was pursuing when I first started out all those years ago, which is to say–anything and everything. The difference is, I now have the expertise I lacked back then, so I am able to show my viewers what I saw in my mind’s eye before I released the shutter. That’s a good feeling, but it doesn’t mean that I feel I’ve reached some kind of photographer’s Nirvana; I am excited to see what kind of curve my vision will throw me next.

Digging Through The Archives

I have been stuck in the Photographic Doldrums for the past couple of months, so I have been spending quite a bit of time searching my archived images. I’m not one to live in the past, but I’ve found that it can be rewarding to revisit my older work. I have rediscovered some of my best work rummaging around in old files. I have also found photographs that, for some reason didn’t make the cut when I first edited them, but over time, with my ever-changing vision and some changes in my workflow, they suddenly take on a new life.

This first image was taken in Canyonlands National Park in Utah. Mesa Arch is an iconic location for landscape photographers, but the shot almost everyone takes is of the sun rising behind the arch. Being a bit of a crank, and wanting to make an image that spoke of my vision and not some other photographer’s, I made this photograph in the late afternoon and used the arch to frame the incredible landscape that lies beyond it.

I made this image of Shiprock while driving to Utah a couple of years ago. I was drawn by the bright yellow rabbitbrush and I was also going through what I like to think of as my “fence phase”. These two elements made the perfect foreground for the great volcanic plug and brooding skies.

This is an image of the Virgin River in Zion National Park. The overcast settled lower and by the next morning, the rain was continuous, making my hike to the Subway impossible due to high water and flash flooding. But this moment, looking down canyon with the soft light penetrating the swollen sky is one of my best images from that trip.

Twilight at Chupadera Pond in Bosque del Apache NWR. These three cranes were hunting for their dinner. They had just flown back from a day of foraging in the farm fields at the northern end of the refuge and now they were continuing their seemingly endless search for food in the pond where they would spend the night. The color of the light in this image has not been altered. For one magical moment between sunset and the onset of night, the entire landscape was bathed in this golden-orange glow.

This final image of the Egg Garden in the Bisti Wilderness has gone through numerous iterations and I think I finally have it just where I want it. I know the composition goes against the venerable “Rule of Thirds”, but sometimes it’s good to break the rules, and sometimes it’s good to revisit the past.

The Ancient Ones-Canyon de Chelly

Canyon de Chelly is unique in many ways. It is the only National Park that is contained entirely within a separate sovereign nation: the Navajo Reservation. It is administered by the Park Service, but access is controlled by the Navajo people. There have been people occupying Canyon de Chelly since the days of the Anasazi, making it one of the oldest, continuously inhabited settlements on the North American continent. Members of the Navajo Nation still live and farm the fertile canyon floor, but it has also been home to the ancient Puebloans, and the Hopis.

This first image was made from an overlook on the north rim. It is the point where Canyon del Muerto and Black Rock Canyon meet – Canyon de Chelly National Park is actually made up of several canyons, the two main ones being Canyon de Chelly and Canyon del Muerto.

This first image was made from an overlook on the north rim. It is the point where Canyon del Muerto and Black Rock Canyon meet – Canyon de Chelly National Park is actually made up of several canyons, the two main ones being Canyon de Chelly and Canyon del Muerto.

There are many ruins within the Park, some are located right on the canyon floor like the Antelope House Ruins, which are located at the base of a towering sandstone wall that served as a huge heat sink in the winter. It was inhabited between about 850-1270 CE, and contains about 90 rooms. The remnants of several kivas can be seen in the bottom center of the image. They appear as distinct round structures.

There are many ruins within the Park, some are located right on the canyon floor like the Antelope House Ruins, which are located at the base of a towering sandstone wall that served as a huge heat sink in the winter. It was inhabited between about 850-1270 CE, and contains about 90 rooms. The remnants of several kivas can be seen in the bottom center of the image. They appear as distinct round structures.

Other ruins are situated high on the walls of the canyon. The Mummy Cave Ruins are located on a shelf which is nestled in a cave three hundred feet above the canyon floor. It is believed to have been continuously inhabited for over a thousand years. Its name comes from the many well preserved burials discovered at the site.

Other ruins are situated high on the walls of the canyon. The Mummy Cave Ruins are located on a shelf which is nestled in a cave three hundred feet above the canyon floor. It is believed to have been continuously inhabited for over a thousand years. Its name comes from the many well preserved burials discovered at the site.

This last image is a view down Canyon del Muerto from the Massacre Cave Overlook. I realize that, visually, it is a bit confusing, but I was attempting to show the complex structure of the rock strata and this location seemed to be the best place to achieve that.

This last image is a view down Canyon del Muerto from the Massacre Cave Overlook. I realize that, visually, it is a bit confusing, but I was attempting to show the complex structure of the rock strata and this location seemed to be the best place to achieve that.

This was a drive-by shooting so to speak. anyone who is familiar with Canyon de Chelly will realize that these images were all taken from the North Rim. I plan to return soon to shoot the other side of the Park. So, look for Vol. 2 in the near future.

The Road And The Sky-Vol. II

When I was a much younger man, I spent a great deal of time standing by the side of a road with my thumb in the air spurred on by the likes of Jack Kerouac and Edward Abbey. Some of those roads were paved and four lanes wide; some were dirt or gravel and you couldn’t really tell how many lanes wide they were. I guess it really didn’t matter as long as they seemed endless.

These days I’m somewhat tamer in my ways, but I still get a feeling of expectancy when I look through the windshield and see nothing but the road, the sky, and a wide open or unknown landscape. Until recently, however, I would not allow the hand of man to enter the world of my landscape photography, so the roads were banished.

These days I’m somewhat tamer in my ways, but I still get a feeling of expectancy when I look through the windshield and see nothing but the road, the sky, and a wide open or unknown landscape. Until recently, however, I would not allow the hand of man to enter the world of my landscape photography, so the roads were banished.

Now that I’ve overcome my phobia of including anything that smacks of man in an image, I am free to express my love of the open road in my photography. As I’ve mentioned in an earlier post, I am working on a project; I am making images of highways and byways as I travel around on my photo excursions. I hope to accumulate enough good photographs to publish a book. The images in this post are ones that have made the cut; some have been displayed in previous posts, but most of those have been re-worked to bring them up to snuff.

Now that I’ve overcome my phobia of including anything that smacks of man in an image, I am free to express my love of the open road in my photography. As I’ve mentioned in an earlier post, I am working on a project; I am making images of highways and byways as I travel around on my photo excursions. I hope to accumulate enough good photographs to publish a book. The images in this post are ones that have made the cut; some have been displayed in previous posts, but most of those have been re-worked to bring them up to snuff.

My expectations of my own work have been becoming higher lately and because of that, I have been forced to either discard or re-process images that I was, at one time, happy with. Evolution.

My expectations of my own work have been becoming higher lately and because of that, I have been forced to either discard or re-process images that I was, at one time, happy with. Evolution.

The only down side to all this road photography is that I seem to be spending a lot of time standing or kneeling in the middle of some very busy highways. Most of the time though, I’m on a road like Indian Rte. 13 or NM 16 which see very little traffic.

The only down side to all this road photography is that I seem to be spending a lot of time standing or kneeling in the middle of some very busy highways. Most of the time though, I’m on a road like Indian Rte. 13 or NM 16 which see very little traffic.

And, at other times, I find myself on unpaved roads such as BLM 1103 in the Rio Puerco Valley, or small access roads like the one in the photo of the Shiprock Lava Dike below where I could stand for hours or even days without being in danger of becoming road kill.

And, at other times, I find myself on unpaved roads such as BLM 1103 in the Rio Puerco Valley, or small access roads like the one in the photo of the Shiprock Lava Dike below where I could stand for hours or even days without being in danger of becoming road kill.

No matter if it’s a paved four lane or an unpaved ranch road, the idea is to get on down the road, maybe to a place where you’ve never been before, and that’s where the magic lies.

No matter if it’s a paved four lane or an unpaved ranch road, the idea is to get on down the road, maybe to a place where you’ve never been before, and that’s where the magic lies.

The Fallen

I made this image at the Santa Fe National Cemetery. I’ll just allow the image to speak for itself.

Out There In The Rocks-Ah Shi Sle Pah Wash

I haven’t been to Ah Shi Sle Pah for nearly two years, but we went out there yesterday to try to locate a rock formation that has been eluding me for some time now.

Ah shi Sle Pah is a dry wash that runs from east to west through the San Juan Basin about thirty miles northwest of Chaco Canyon. Over the course of millions of years, the run-off has eroded the soft mudstone leaving the harder sandstone balanced precariously on the remaining mudstone columns. These bizarre fformations, referred to as hoodoos can stand for thousands of years before finally yielding to erosion and gravity.

Ah shi Sle Pah is a dry wash that runs from east to west through the San Juan Basin about thirty miles northwest of Chaco Canyon. Over the course of millions of years, the run-off has eroded the soft mudstone leaving the harder sandstone balanced precariously on the remaining mudstone columns. These bizarre fformations, referred to as hoodoos can stand for thousands of years before finally yielding to erosion and gravity.

The sandstone that is slowly being exposed by erosion was formed in the late Cretaceous period when this area was a tropical forest with rivers which served to compress and cement the sand particles into the sandstone we see today. There are petrified logs lying about as if carelessly tossed aside by some giant prehistoric toddler.

The sandstone that is slowly being exposed by erosion was formed in the late Cretaceous period when this area was a tropical forest with rivers which served to compress and cement the sand particles into the sandstone we see today. There are petrified logs lying about as if carelessly tossed aside by some giant prehistoric toddler.

One of the things I find intriguing about Ah Shi Sle Pah is the variations in the visual texture of the place. It is a photographer’s dream come true. The erosion channels in the mudstone are a never -ending source of delight for me.

When the light hits these incredible features in a certain way, especially early or late in the day, the side-lighting makes the textures jump out and the whole scene is electrified with a sense of other-worldly drama.

Did I find the formation I was searching for? Well, I have to confess that I failed, but that’s alright. I guess I’ll have to go back another day.

A Desert Rat’s Journal-Chapter 2

Being a desert rat in New Mexico is a full time job; there are so many places to polish your craft. One of my favorites is the Rio Puerco Valley. The Rio Puerco is a mostly dry riverbed that winds its way through some spectacular country on its way to join the Rio Grande.

This is the view looking south from BLM Rte.1114. It is a primordial landscape, dotted with volcanic cones and with the addition of a stormy sky, it becomes a journey to the time of dinosaurs if you disregard the cattle-guard in the foreground.

One of the things you can find without too much trouble (unfortunately) is trash. It comes in all shapes and sizes. This piece of culvert, with catch basin attached, is the extra large variety. It lies slowly rusting into the earth with Cerro Cuate as a silent witness.

There is also an abundance of old tires in the valley. They can be found serving as containers at watering holes, on the roofs of old trailers, or as in this case, ornamental artwork hung on a cattle-guard.

But, regardless of the trash, cattle, and other abrasive signs of man, there is much beauty to be found in this unique landscape. I will soon be adding The Rio Puerco to my High Desert Photo Tours line-up.

I made this last image from an overlook near Cerro Cuate. There are no rock walls or steel stanchions at this overlook, so you must be careful. In a place like this, the buzzards will find you long before a rescuer.

Time, Wind, and Water

If you’ve never been to the desert southwest, you may not be aware of the importance of water to the landscape. Not only is it the source of life for the many hardy species that call this arid environment home, but is also one of the main forces by which the landscape came to be what it is.

These first three images were made in Blue Canyon on the Hopi reservation in northeastern Arizona. Over eons, a small stream and countless windstorms have sculpted the soft sandstone leaving a wonderland of deep chasms and etching the stone with amazing textures.

Just in case you have the idea that this small stream doesn’t have its moments of glory, here is an image of a car that was carried away while the rivulet was in flood. It is now wedged firmly between the walls of the water cave.

This is the place where the stream plunges into the chasm it has carved out over the course over millions of years. I had posted this image in a previous blog about my trip to Blue Canyon, but that was a color image. I made this black and white conversion using Silver Efex Pro and put some emphasis on the structure and texture to show the wrinkles time has etched into the face of this desert landscape

And just so you know that we have our fair share of “Erosion Art” in New Mexico, here is an image I made recently in the Mesa de Cuba badlands in the northwest corner of the “Land of Enchantment”.

These places can mean different things to different people: Some may look at such a place with a mix of wonder (wonder that anyone could find beauty there) and fear-fear of the unknown, fear of what may be lurking around that next bend, and fear that somehow they may, as I did, develop a deep sense of love and respect for such a harsh, unforgiving environment. One thing is certain if you take the time to look around you and think about how things work in a desert ecosystem, you will come away looking at life a little differently from the way you did before your visit.

Happy wandering! Oh, bring a GPS and plenty of H2O.

A Desert Rat’s Journal

I am a self–proclaimed desert rat; there is something about the harsh, elemental landscape that touches my spirit and makes it soar. It’s little wonder then that I recently found myself back in the Bisti Wilderness loaded down with cameras, lenses, my tripod and my GPS (not to mention plenty of water). I had an agenda: there are several well-known landmarks that, for some reason, I had not yet photographed–at least not to my satisfaction.

Robin and I set out from the parking area with our sights set on the Brown Hoodoos, the first on my list. I had GPS coordinates, but it’s not that easy. It seems a frontal approach was not the way to reach our goal; there were too many obstacles and too much fragile ground to make this route acceptable. So, we made a flanking maneuver, gained the elevation we needed, and approached from the rear. It still took several aborted attempts before we reached the hoodoos, but it was well worth the effort.

I made this image from the place where we first came upon the Brown Hoodoos. I call it “The Valley Of The Earth Gnomes”. I was struck by the implied activity taking place. Even though nothing was actually moving, it seemed we were gazing down upon a small village going about its day to day routine.

I made this image from the place where we first came upon the Brown Hoodoos. I call it “The Valley Of The Earth Gnomes”. I was struck by the implied activity taking place. Even though nothing was actually moving, it seemed we were gazing down upon a small village going about its day to day routine.

After leaving the hoodoos, we headed for the Egg Garden. I had been there many times, but I couldn’t resist stopping by to see what images might be waiting for an enterprising photographer. I found the Queen Bee right where I left her months before, but the atmospheric conditions were much better than any I had encountered there previously.

After leaving the hoodoos, we headed for the Egg Garden. I had been there many times, but I couldn’t resist stopping by to see what images might be waiting for an enterprising photographer. I found the Queen Bee right where I left her months before, but the atmospheric conditions were much better than any I had encountered there previously.

The next place on my list was the Eagle’s Nest. The Nest is another mile and a half beyond the Egg Garden and as we walked, the clouds began to gather. By the time we got to our destination, it was spitting rain. There was also lightning; I began to worry about our exposed situation and the nearly five mile trek back to the car. Still, I couldn’t help but wish for a lightning strike as I composed this image. I call it “My Inclement Muse”, a nod to the force that sends me off into such places in such weather searching for beauty.

The next place on my list was the Eagle’s Nest. The Nest is another mile and a half beyond the Egg Garden and as we walked, the clouds began to gather. By the time we got to our destination, it was spitting rain. There was also lightning; I began to worry about our exposed situation and the nearly five mile trek back to the car. Still, I couldn’t help but wish for a lightning strike as I composed this image. I call it “My Inclement Muse”, a nod to the force that sends me off into such places in such weather searching for beauty.

As we began retracing our steps back to the parking area, the rain stopped and the clouds lifted a bit. I still had one location on my list that I had not been able to find, and I had already decided that the Bisti Arch must have collapsed. I had previously come across a spot that looked like it could have been the arch, but it was nothing more than a pile of rubble when I found it. As we walked past the place where the arch was supposed to be, I turned to have a look back at the way we had come, and there it was. It was much smaller than I had imagined it to be; that’s the reason I had had so much difficulty locating it. As I set up my camera and tripod, everything came together. It was as if the muse was rewarding me for my diligence.

As we packed our gear into the car for the ride home, I was overcome by an emotion not unlike the one you might feel after finishing a good book: satisfaction mixed with melancholy. I had completed my Bisti bucket list. Then I realized that there are still many surprises hidden in a place like the Bisti; I knew then that I could easily spend the rest of my life out there and still not uncover all of the little known treasures stashed away in the washes, slot canyons, and rolling bentonite hills of such a place.

Black and White, Toning, and Split Toning

When you convert an image to black and white, your creative options don’t end there. There are several ways to convey the mood of a black and white image, and strangely they involve color. Anyone who is interested in presenting their photographs in black and white should begin by learning the best way to make the original conversion. Perhaps the most direct method is to convert the image to grayscale using the command in the Image dropdown menu in Photoshop, but easiest is not always best. Before I go any further, let me acknowledge that there are many image editing applications out there, but for the sake of simplicity and because Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop are the applications I use, I will limit this discussion to those two.

A much better way to make your conversions is to add a Black and White adjustment layer in Photoshop, or if you’re working in Lightroom, use the B&W conversion tab in the Develop module. In either case, you will get a series of sliders which include all the colors in the spectrum from red to magenta. By using these sliders, you can adjust the tone of each color as they appear in black and white. In other words, you have much more control over the contrast and tonal range of your monochrome image.

If you want to take your image a little further, you can tone it by checking the tint check box in the B&W adjustment panel in Photoshop. In Lightroom, you can apply the toning by using the Split Toning panel in the Develop module. The image above has a sepia tone applied to it. I normally use at least a small amount of toning on all of my black and white conversions, but if I want to convey a certain feeling, I will use more saturation in the toning. I normally use either a sepia or a selinium tone, but you are not limited to these; you can choose any hue across the spectrum.

Finally, you have the option of doing a split tone. This is done by choosing a tone for the highlights and one for the shadows. There is no option for split toning in Photoshop. It must be done in either Lightroom or Adobe Camera Raw. Using the sliders in the Split Toning panel, you can adjust the hue and the saturation for each of the tones you choose. The above image has a very slight yellowish tone in the light areas, and a bluish (selinium) tone in the darker areas. I chose to use a split tone for this portrait to add a little more visual contrast and interest in the horse’s face.

This last image is one that I used in a recent post. I am re-posting this color version for comparison.

I chose to make a sepia toned B&W conversion and I think this does a better job of conveying the feeling of melancholy that I had when I first encountered this scene.

I chose to make a sepia toned B&W conversion and I think this does a better job of conveying the feeling of melancholy that I had when I first encountered this scene.

So, the next time you find yourself wondering if your image might look better in monochrome, take some control over the process. You may come away pleasantly surprised.

Shiprock-The Big Plug

New Mexico is a geologic wonderland. Much of the earth is laid bare by erosion, both wind and water sculpt the land removing the softer material and leaving the harder stuff to stand as enormous monuments to a time long past. Shiprock in the northwestern corner of the state is what remains of a volcano that erupted about twenty-seven million years ago. It now stands at a height of nearly sixteen hundred feet above the flatlands which surround it. The monolith is sacred to the Navajo people and it plays a large part in some of their creation stories.

I made this first image as we approached Shiprock from the west. I saw this as a great addition to my byways project; it also puts Shiprock in perspective in relation to its surroundings. The plain stretches for miles in all directions and the great volcanic plug is virtually the only-and certainly the biggest-thing to break the horizon.

As we got a little closer, there was a herd of ponies grazing peacefully with Shiprock in the background. Close by stood a trailer with a small addition. I assume these horses belong to whomever lives there. What a great backyard!

This last image was made after we drove through the breech in the largest lava dike. It is one of six that run for miles in all directions away from the central column. These dikes were underground lava tubes at the time of the eruption, they now stand high above the ground, like Shiprock itself, exposed by time and the elements

Give Me A Dramatic Sky

If you’re a landscape photographer, there is nothing worse or more boring than a clear blue sky. Don’t get me wrong, I love a crisp autumn day with cerulean skies as well as the next person, but when I’m out making images, I want some drama from above.

Luckily, here in New Mexico, we get nearly as many days with stormy skies as we do with clear ones. I have always been deeply affected by the weather; when the barometer drops and the sky closes in, I get gooseflesh and I’m out the door with my camera and tripod.

Luckily, here in New Mexico, we get nearly as many days with stormy skies as we do with clear ones. I have always been deeply affected by the weather; when the barometer drops and the sky closes in, I get gooseflesh and I’m out the door with my camera and tripod.

The first two images were made in the Rio Puerco Valley which is quickly becoming one of my favorite places to photograph. There are over fifty volcanic plugs, wide vistas, and beautiful stormy skies. The color photograph above is of the Rio Puerco, a (mostly) dry river for which the Valley is named.

The first two images were made in the Rio Puerco Valley which is quickly becoming one of my favorite places to photograph. There are over fifty volcanic plugs, wide vistas, and beautiful stormy skies. The color photograph above is of the Rio Puerco, a (mostly) dry river for which the Valley is named.

This last image was made near the small village of Torreon, NM. I had driven past these ruins many times, but on this day something told me to stop. The result was several good photographs, this being my favorite of the bunch.

This last image was made near the small village of Torreon, NM. I had driven past these ruins many times, but on this day something told me to stop. The result was several good photographs, this being my favorite of the bunch.

So, the next time you see a storm brewing, grab your gear and head out to make some images. Oh, and you might want to bring a raincoat.